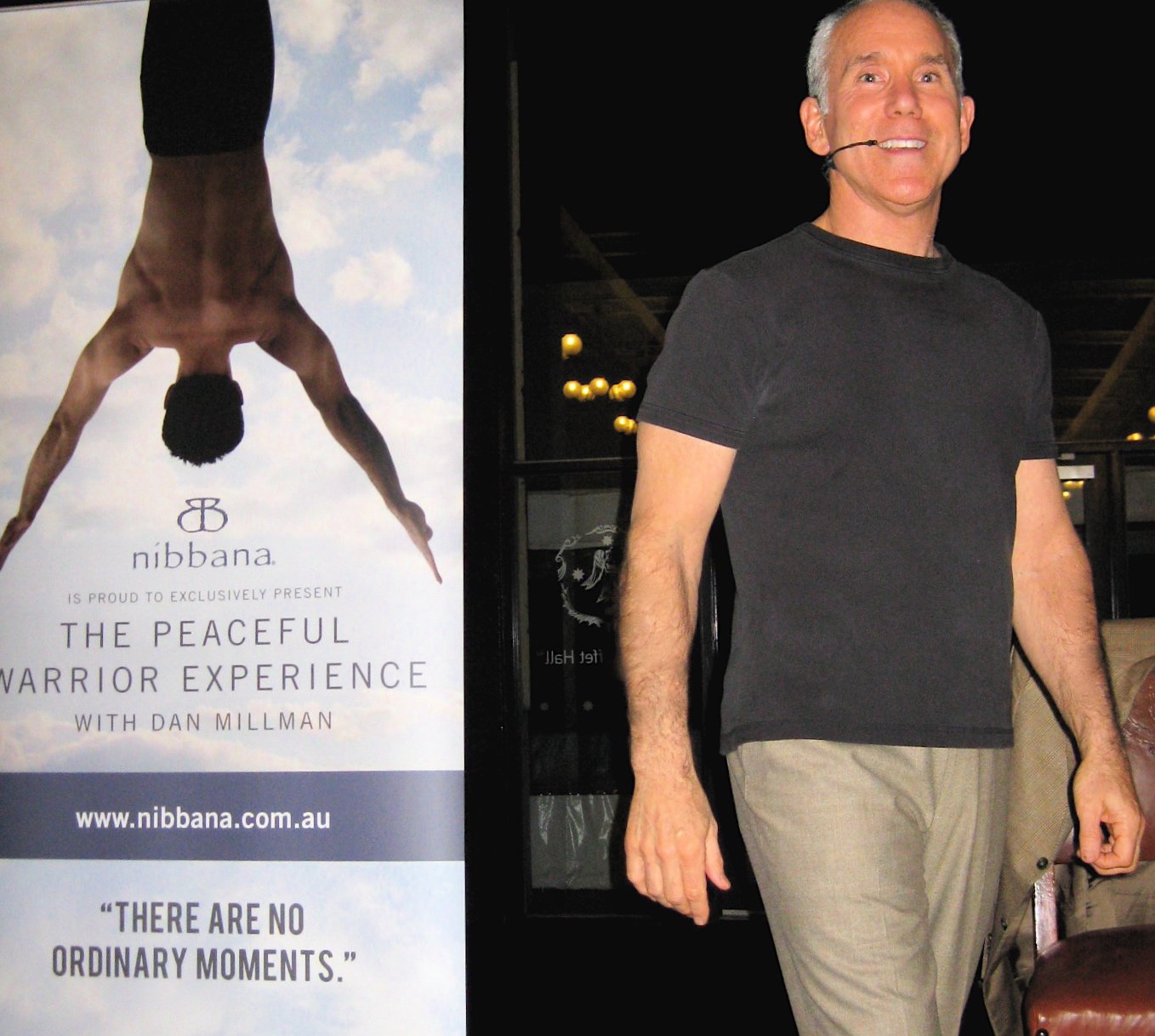

Episode 672 - Mr. Dan Millman

Mr. Dan Millman is a former world champion athlete, author, university coach, martial arts instructor, and college professor.

To me, I was an athlete so I appreciated sports. In sports, you could lose a point or lose a match. In Martial Arts, it comes from a more sincere lineage. Where before it was a sport, it was about life and death. So, no martial artist could simply focus on physical skill alone.

Mr. Dan Millman - Episode 672

For a person who doesn’t like to hit and be hit, boxing wasn’t the thing for him. Mr. Dan Millman found Judo growing up for the same reason that many of us went into Martial Arts, bullies. Mr. Millman, exposed to eastern and Japanese thought early in his life, later on, developed the Way of the Peaceful Warrior which is the central theme of his books. Aside from Judo, Mr. Millman trained with Karate, Aikido, and other self-defense arts as well.

In this episode, Mr. Dan Millman talks about the way of the peaceful warrior and his journey as a martial artist. Listen and join the conversation!

Show Notes

You may check out Mr. Dan Millman’s books including the Way of the Peaceful Warrior at peacefulwarrior.com/books/

Show Transcript

You can read the transcript below.

Jeremy Lesniak:

Dan Millman, welcome to whistlekick Martial Arts Radio.

Dan Millman:

Thank you, Jeremy. Good to be here with you.

Jeremy Lesniak:

It’s great to have you. The show itself is about six and a half years old. I’ve known some of the guests that have come on for a long time, but there is nobody that has come on who I’ve known of for a longer delta between knowing who they were and getting to talk with them, so this is kind of exciting for me. Thank you for the honor of your time.

Dan Millman:

My pleasure, really.

Jeremy Lesniak:

Now some of the folks who are listening may know your name, but they are probably not going to know much about you and your relationship to the martial arts. I know you have talked bits about it, you’ve hinted at it, and anybody that knows you work knows that this has been a part of your journey. But this is our opportunity to go deep into it and that’s what I’m excited about.

So let’s start here: If we think about when you started martial arts, there must have been a point where you were aware of martial arts. Do you remember your first memory or awareness of martial arts and that it existed?

Dan Millman:

I do. As a matter of fact, in my entree to the martial arts began. Maybe as many young people's time in the martial arts begin. I faced some childhood bullies when I was eight, nine, 10 years old in elementary school and middle school primarily. Mm-Hmm. And. After several encounters, I asked my dad if I could learn some self-defense. And even though I'm known by many people as a former gymnast, people have seen the Peaceful Warrior movie based on my first book. I actually began martial arts before gymnastics. My father took me to a boxing gym he knew of, where I quickly discovered I didn't really like getting hit or hitting other people. So I didn't pursue as a 10 year old, or maybe it was nine year old, but I didn't pursue boxing. Then he took me to a Japanese part of town and my first judo dojo. Judo, the gentle way was my first introduction to the arts and very good teachers. I loved learning rolling and falling and various throws. That was my first study several times a week. In fact, it was a big, red-haired giant, big hearted guy who let the kids throw him around. His name is Gene LeBell, whom I think you've probably heard of and many of your listeners have.

Jeremy Lesniak:

I know of Mr. LeBell, yes.

Dan Millman:

Great guy. So I was exposed to him early on and in my first tournament I tried tomoe nage, which is like a circle throw where you lay backward, put your foot on someone's stomach and grab their lapel and throw them over your head. It used to be used in the movies a lot; it looked good. It didn't work very well for me. This young boy, my age, was heavier than I was, and my foot slipped and he fell on top of me and pinned me. That was my exposure to my first martial arts experience in a competition which I actually surprisingly didn't really care for much. I loved the training. I loved the terms and the rolls and the philosophy - as much as one 10-year-old can absorb. So that was my first exposure.

The way I discovered judo was in our neighborhood in Los Angeles, there were many, many Hispanic and Asian people, and where we used to play up in a forest of trees was taken down and there was a Japanese Cultural Center built there right up our street. And so I was exposed to things Japanese and my first role model, he was a streetwise kid. He was about 13 and I was only 10. His name was Steve (USAW?) I used to see Japanese dolls in his house, these geishas and there were other artifacts, there was a samurai sword.

So, I was kind of exposed to Eastern thought Japanese, particularly in judo early on. I'm not going to go into that much detail because we've all had our history of in the arts- either training in one art or many.

I did later on take some karate with my cousin. In high school, I got pretty immersively involved with Okinawa-te with a man named Gordon Doversola. Whether someone has heard of Gordon or not, he actually choreographed that first fight scene in the original movie of The Manchurian Candidate. Maybe you remember that (yeah) was one of the earlier good martial arts fight scenes with Frank Sinatra, I believe.

Jeremy Lesniak:

Some have called it the first martial arts fight scene on film in the modern era.

Dan Millman:

I think James Cagney did some judo in one of his earlier films. It might have been one of the first time an Asian martial art was used other than just fight this fighter. But yes, it was an early one, and it was one of the better fight scenes. So Gordon choreographed that, but still, he was an excellent teacher. I learned the 108 move Falling Leaf form. Okinawan martial arts, as many of your listeners know, blend the linear style of Japanese karate and the more circular Chinese wushu type kung fu form. It's a very interesting style, and I just happened to be exposed to that in high school.

Then I had a latency period of 10 years where I didn't really do martial arts, but I did get a seventh degree black belt from the trampoline because I got into gymnastics. In fact, the first day in gymnastics class, it was a club, a tumbling and trampoline club, in my middle school, my homeroom teacher started it. She asked if anyone could demonstrate a roll and my hand shot up. I was so enthusiastic and what I did was my judo roll, and I was very embarrassed when she said, “Oh well, actually, in acrobatics, we do a roll directly forward over our head.” So I learned the difference between those types of rolls and I've learned many others, of course, since.

And later on, after I started coaching at Stanford University in gymnastics, I took up aikido. I ended up getting a shodan certificate. So now if I'm ever attacked on the street, I can whip out my certificate, maybe give someone a paper cut. Still, I consider myself a real beginner in aikido.-I love the philosophy, the physical movement of non resistance, getting out of the way. Of course that's the principle for any art. But the circular motions and the friendliness of it. Every art has its strengths and liabilities. I once asked my aikido sensei, Robert Nadeau, who taught George Leonard, who was well known for his philosophy. He's an author. Anyway, I asked him, “You know, can you really learn to defend yourself on the street with aikido?” This was before Steven Seagal. (laughter) He said in his grumbling kind of raspy voice, “You want to get self-defense, get a piece, you know, get a gun.” So he was very practical in his approach. But then he body slammed me to the mat, I guess to make a point.

But after that, I took up tai chi and learned a 108 move form on both sides right and left. I also dabbled with the basics of kali, escrima, arnis, the Filipino arts, in order to teach a personal growth training for 14 years, using knife fighting as a means of self-knowledge and personal growth and making some shifts. It's a great metaphor.

And finally, I guess one of the most interesting arts I ever studied was with a fellow who is really good at pak silat. he was an instructor. Twenty seven years doing this, he was very fast, named (Al mc….). He lives in the Midwest. I just took a seminar. This guy named Vladimir Vasiliev and this thing called Systema, and I'd never heard of it. But he said, “You really want to do this.” I ended up flying to Toronto, training with Vladimir for a couple of weeks. and really sore. But again, it's not a macho art, but it's very demanding physically and it was tremendous experience. And later I went to Moscow with the Systema, a group trained with Mikhail Ryabko, one of Vladimir’s colleagues and teachers as well. Yeah, he's amazing.

Jeremy Lesniak:

I've heard that. We've had a few folks on the show of trained directly with him, and they have nothing but amazing things to say.

Dan Millman:

Well, you know, there's a saying about Koichi Tohei and Aikido and also Ueshiba , the founder of Aikido, they said the difference between Tohei and Ueshiba is with Tohei you feel like you're trying to move a mountain. With O-sensei Ueshiba, it's like trying to move a feather and not being able to do it. So there is a certain different quality, and Vladimir is an amazing practitioner of Systema, as he's demonstrated many times with challenges. Ryabko doesn't even look like he's fighting. You just isn't there when you try to attack him and you're pinned and thrown whatever. He's amazing. Well, you've probably heard stories about that, but I'm just sharing a bit about my experience in the arts. And I went later to a training camp north of Toronto, Canada, where we were fighting in the water and in open spaces, in forest and night. All kinds of interesting environments, testing our intuition, all that sort of thing.

I owe a great debt to the martial arts. And the reason I mention this is because, as many people know, not everyone. I wrote a book called Way of the Peaceful Warrior, and it's become quite popular over the last … well since 1980, when it first came out in hardback. And some people say, “Well, why do you use the term ‘warrior’? You were a gymnast, weren't you? So at least I had some grounding in the martial arts. I wouldn't say depth, but I did have breadth, a sense of perspective about the strengths and limitations of various arts and the understanding how self-defense is different from martial arts. There's martial science, martial art. I also trained with Matthew Thomas, who started model mugging. You may have heard of that self-defense system where the guys wear these overalls heavily padded and they teach full contact reality-based scenarios. And that evolved into FAST defense. FAST stands for fear adrenal stress training with a recognition that when you're under high stress, the fancy moves don't work. You need high percentage shots, large muscle groups and it's very practical is the best self-defense training per se, I’d ever had. A fellow named Bill Kipp, former Ranger, and many, many years in the martial arts was trained by Matt and then evolved it further. . Anyway, that's the background, so I can talk with at least some authority about the idea of warriorhood, budo, bushido and the philosophy.

To me, I was an athlete and I appreciated sports. In sports, you could lose a point. You can lose a match in martial arts. It comes from a more sincere lineage where before it was a sport, it was about life and death. So no real martial artist could simply focus on physical skill alone - what if emotions were in turmoil or the mind distracted. I think there was a holistic sort of training from the beginning in martial arts where you had to train body, mind, emotions, spirit. That's one thing I appreciate that lineage of the arts and it's really about life. You know, it's funny in The Karate Kid, Pat Morita could get away with his character. You know, Mr. Miyagi could say, “Karate like life” and that's it. I mean, the road. The difference between expertise and mastery in my view is that in expertise you become physically skilled, but mastery even on beginning levels, if someone recognizes my training is really a training for life through the art, whatever that art may be, they are in the path of mastery. That's what connects it all up, I think.

I was an assistant professor of physical education at Oberlin College after my coaching career at Stanford University for four years. I coached the top U.S. Olympian elite, turned the team into one of the top three teams in the U.S. in about three and a half years. And I left to do more creative work in a sense at Oberlin College. I taught courses like psychophysical development and mirthful movement, circus course,, juggling and teeter board acrobatics and so on. But I created a course that introduced students to both the basic elements of Taichi and Aikido. And for the catalog. I was going to call it “The Way of the Warrior,” which makes a lot of sense. We understand way meaning do or tao on a path to excellence and so on through training. But it didn't quite fit because these are a bit more internal arts, and they were not primarily aggressive arts, but defensive. Both of them. And so I ended up coming up with the idea. I said, “Wait a minute, I'll call it way of the peaceful warrior.” And this was the first time that I organically came up with the term. And it was only years later when I wrote the book that I said, “Hey, you know, what is this book going to be about? Like one of things living in the present day and so on and so forth.” And I said, “I'll call it The Way of the Peaceful Warrior.” And it stuck. That's another story, but that that kind of connects up for those who don't know my work, how I came up with the term peaceful warrior. And I probably should mention that I view everyone as a peaceful warrior in training. And what I mean by that is it's not some namby-pamby, new agey kind of label. I've never seen anybody who isn't striving to live with them with a peaceful heart, to live with a sense of serenity. Equanimity in the amidst the chaos of the daily news. And the challenges of everyday life. But also there are times we need to acknowledge that there are times we need a warrior spirit. And it's not necessarily about combat, except in the sense of the inner battle that sometimes goes on with demons of insecurity, fear of one kind or another, anxiety, self-doubt. But really, it's about standing up tall inside of ourselves and marching into life, rolling up our sleeves, tackling what we need to face in everyday life. And we all face adversity. Sometimes small, sometimes major – loss, grief, challenge, illness, accidents, various kinds of physical, emotional and mental pain. We've all had it. And so this is why I view all of us as peaceful warriors in training in the school of everyday life. So the term isn't some exclusive club you can join. You don't have to get some special initiation to become a peaceful warrior. It applies to human beings on planet Earth, which I view as a divine school for souls. Daily life is our classroom, so I hope that it gives a sense of a context where I'm coming.

Jeremy Lesniak:

There are about a hundred directions that we could go and question swimming in my head, which one to choose for. So I think I've got the one. And we're going to we're going to roll back a little bit. You talked about boxing not quite resonating for you, but you're talking about this cultural center, you're talking about Japanese arts, Okinawan arts, you're talking about experience with historical cultural elements, even outside of training and then for anyone who's read The Way of the Peaceful Warrior, which I did for the first time quite a long time ago, your approach even to your gymnastics training reminded me of martial arts training, just that mindset. So I'm curious because we’ve found over the years that when someone tries martial arts and finds something that works for them, something that's sticky, there's a reason, there's an element. Maybe it was something that was missing, something that they were dreaming of, whatever it is. So do you have a sense as to what it was when you first found judo that was clicking for you at least better than the boxing was?

Dan Millman:

Hmm. Good question. Some of it is just serendipity and good fortune. They happen to be at or near our neighborhood. My father was willing to take me. It was traditional. The instructors were Japanese, along with Gene, I think also. But he just went to train with us, so I wouldn't say that I made a conscious choice at 10 years old to find it art that resonated with me. And later, by the way, I did a little bit of boxing again. I dropped in to Peter Ralston's in Berkeley, has his place in Oakland, and again found out. I really didn't like getting hit much. I got hit a lot because these guys are much faster and better than I was. Whereas judo was more friendly, I used to like to wrestle as a kid and try to get out of holds. I mean, if I discovered Brazilian jiu jitsu, which I'm going to introduce my grandson to in a couple of weeks when things quiet down as far as our current situation. I probably would have liked that very much. But it was something about just moving with someone and trying to use leverage. That's what impressed me. You see, I never heard of judo, but I saw that exhibition at the Japanese Cultural Center and I saw kids and small people throwing larger people. And I'd always been small for my age, and I was one of the youngest kids in my class. I started school early with kindergarten, and from then on I was one of the younger ones. I explain all this in my new memoir called Peaceful Heart, Warrior Spirit, appropriately. Seeing how small or people can throw larger ones, I said, “I want some of that.” So that's probably what attracted me to try judo. It wasn't overall size and strength, but to a large degree leverage. And that's why I was attracted to that.

And again, you said, Jeremy, that many people, you know, follow one art for a long time because they resonate with it. There are people who pick one thing and go in-depth and continue it for many, many years, even decades. And my interest somehow instinctively was not conscious, really, I just like to be exposed to different kinds of approaches, to movement, to self-expression, as Bruce Lee used to say. And so it gave me an appreciation for the various arts and their strengths and so on. I get the sense of discernment about the different arts and by the way, one of the one of the prime principles in this approach to living that I teach, called the peaceful warrior's way, is that there is no best martial art, no best teacher, no best book, no best religion, no best philosophy or path or diet or system of exercise. There's only the best for each of us at a given time of our life. So I have a respect for people's individual choices and their process. And what I've asked by people, and I am very often. “Dan, can you recommend a martial art for me to study?” I say, “Well, yeah, look, Google, what's near you? First of all, because I can tell you a great school that is 300 miles away. It's not going to be very practical.” Sure. And second, find a really good teacher where the students seem to be having a really good time. They're getting a lot out of it. A sample of class observe and also partake and pick a teacher that you resonate with. The style perhaps is less relevant than the teacher, and some teachers teach an art or subject in school. Others teach life through the art, through the teacher. And that's what I would look for.

Jeremy Lesniak:

I'm smiling. I suspect a number of the listeners are laughing because you're hitting all the points that I hit when that subject comes up. You know, people lead with style, and that's the least important of all the things you can go through. It's pretty much the least important. And just as you said, where are you? When do you want to train? What's your what's your reason for training things like that? You're talking about your entry to martial arts with some passion, with some conviction, and yet you set it down for gymnastics, which makes me wonder. Did you see gymnastics as something completely different or maybe something that had far more similarity than maybe someone who hasn't been a gymnast might notice?

Dan Millman:

Well, strangely enough, for a national and world champion on the trampoline to say, but I've never really liked competition. (laughter) I like collaboration. I like working with people. I also tended toward individual endeavors where my success didn't depend on someone else's failure. And that's more of a philosophical response to your question, Jeremy.

But actually, what happened was after my exposure to judo. Now that, by the way, I should mention and let me take a step back, OK? First, physical discipline I was exposed to other than, you know, kids running, throwing frisbees, playing baseball and all that. The first discipline that I studied was modern dance. I was about nine years old, I think, before I took judo. My mother played the piano for a modern dance class, and she didn't want to pay for a babysitter. So she brought me and enrolled me in the class. It was me. You can imagine a nine year old boy and about ten or twelve girls. Yeah, I in tights and they were wearing tutus. I refused that, of course. But of. I learned to point my toes. I learned muscular control. I learned about movement, and that was a great foundation for all the physical disciplines I did afterward. So that was the first thing I was exposed to, but also about that age. I was at a summer day camp, going with my cousin and my sister, and she loved horses. She did horses. My cousin did all the things she liked to swim. But I discovered an old, really heavy duty trampoline, ground level trampoline never seen that kind of thing before. But when I started jumping on it, it allowed me to jump like a kangaroo higher than I could on the ground. And to most people today know backyard trampolines are all around everybody. But it was more rare, more a circus thing back then. And so it was rare to find that, and I just spent all my time jumping on that trampoline, trying to do see drops, belly drops, backdrops, and I wanted to learn flip and I was an autodidact. You know, that term I was trying to teach myself. And I kept trying to figure out how to spin around and just before one of the summer camp ended I did such a well-timed front somersault that was trying to get all the way around on my feet while I missed my feet entirely, landed on my face, scraped my whole face up, and I got scabs everywhere. But it didn't even dampen my enthusiasm. However, I didn't discover another trampoline until a couple of years later again, when my homeroom teacher in middle school the first day said, I'm starting a trampoline tumbling and boy, I wish there was something about it. I just knew I had to do. I needed so I'm so enthusiastic and I the previous story I told about doing the roll over my shoulder and the embarrassment led to some a lot of learning handstands, handstands, cartwheels, back handsprings. I even learned to stand on my instructor's shoulders on the trampoline, jump off his shoulders, land on the trampoline, do a backflip to lean back on his shoulders. And this was, you know, I was 11 years old, just starting middle school and that immersed me. I mean, it just completely drew me. And there's more to I tell the more the story in the memoir, but I ended up just getting better and better. And I was doing trampoline at its center in Burbank, California, and I ended up winning the state championship. I was 14 years old and the rest were college students. If anybody wants to look me up a life, I was on the cover of Life Magazine with some friends way back in May 1960. The trampoline craze was beginning their backyard trampoline centers, opening up everywhere around 1960. And so Life Magazine took an interest and they had a picture of me and a bunch of friends doing some trampoline in midair on that cover of Life magazine and inside the 14 year old Danny Millman was doing, demonstrating some flips with strobe lights going off and the trampoline led to tumbling, which led to gymnastics events in high school and a scholarship to UC Berkeley eventually. So I was just immersed in gymnastics and I liked it. There was no fighting and I didn’t have to get punched or hurt. I fell a lot. I mean, I showed a certain toughness that that one it can evoke in the in the martial arts. But it was with the apparatus that was showing spirit and determination and falling again and again.

But I think my early exposure to judo, you know, being comfortable falling and I never minded, but I used to fail 50 times a day, you know, crashing until I learned the move. So failure was a totally different critter to me that many people fear it, but I was so used to failing. I failed my way into success. That's how I trained in gymnastics. But yet when I started coaching, I was doing gymnastics anymore. And so then I thought, maybe I can do some more training in the martial arts, and that's when I happen to find a local school in aikido and one of the foremost teachers. You know, I asked him, I said, you know, Nadeau is like a French name. I said, Are you any good at this? I actually had the chutzpah to ask him that. And then he said, Well, you know what I trained with Uchiha Desi trained with the founder in Japan after the war. And he used to tell me they trained on hardwood floors with nails sticking up, they hadn’t be pounded in improperly. It was tough training, and you probably know this. The beginnings of a lot of martial arts - they only attract the toughest guys, and later when they reach out to more people, they soften somewhat. And then, of course, later they become sports, even though aikido never became a sport.

Jeremy Lesniak:

It's interesting to think of something like aikido, which is seen so gently, so peaceful. Think of thinking of it in terms of rough around the edges in a sense. You talked about this transition from martial arts to gymnastics and you know, we can imagine the things that you bring from martial arts to gymnastics. But I'm also interested about that, that secondary transition. What was it you took from gymnastics into aikido?

Dan Millman:

Yeah. Well, not all good things. For example, when I began doing the aikido moves.., first of all, I was into perfection, symmetry, and control. But when you're dealing with another unpredictable partner, even though, you know, in aikido, they tend to have very rehearsed kind of attacks and defenses. Yeah, ritualized, almost. But still, they kept telling me, relax, Dan, relax. And I was like, I am relaxed because I was used to doing iron crosses and the rings, you know, and planges and all those strength moves. And so I had to unlearn the idea of being totally in control and start to flow and relax and extend energy and ki. If I'd returned to gymnastics after martial arts, it would have been even better. One fed the other. So it took me a while to overcome the whole control thing in gymnastics and learn to just flow and relate to my partner in that way because I was used to being such an individual, even though we had a team. We each did our individual routines. And so working with another person took some adjustment. But yes, definitely the concentration, the focus, the spirit that I learned in training for gymnastics did carry over later to the martial arts of aikido and the others that I practiced. So one thing you know, it's physical movement. You know, we have words, we have yoga. We have football, baseball, sports, martial arts, acrobatics. But what is it all have in common? Movement, attention, stillness and focus, dynamism, a certain dynamism.

So it's really all about expressing yourself again through these different physical disciplines. But really, there's psychophysical disciplines as any martial artist knows, you have to have a certain mental ability, if you will and spirit. Some of my peaceful warrior seminars, the long weekend workshop, sometimes we do board breaking but we do it as a metaphor, not as learning to punch hard or kick hard or whatever. And it's a very powerful metaphor I've found, and it's been used by many people. And I tell this when I train people how to how to do it, you know how to break the board, the techniques and so on. I say I can teach you the technique. I'm responsible for teaching the proper technique to maximize your chances of going through this board. But I say the spirit part is up to you, and I can usually tell who is going to break the board because, you know, they had the eyes of the tiger, they would go right through that board.

And I tell the story in in peaceful heart warrior spirit in the memoir that once I was down in Texas, in Austin, in the Hill Country, a place called the Crossing's, and I was teaching a weekend workshop there and we kind of did a thing on Sunday morning, awaken the warrior spirit. It wasn't a martial arts training, mind you, it's a peaceful warrior training about training the mind, doing some different kind of work, breathing exercises and so on. But on Sunday, we did the board braking. And normally, when asked for a volunteer after I trained them, how to do it, I say, who wants to be first? Normally, some larger guy, you know, maybe martial artist who has some experience will come up first confidently and they want to show their stuff. So but this time this tiny, diminutive woman came up and an elderly woman and she introduced herself as Maggie, and she said she told me several things. First, she said, Today is my 79th birthday. She said I am right-handed, but I've injured my right hand, so I'm going to have to use my left hand and I've never done this before. Well, when Maggie knelt down to bring her hand through that board, it was it was at that time I used the usual traditional pine board, you know, dried pine board. Anyway, I looked in her eyes because I was on the other side and I could see her eyes, and I knew this lady was going to go through that door and she just bam like knife through butter. Which surprised me, actually, because it is easier for people with larger mass to do it. I only learned later that she was a student, of Cheng Man-Ch’ing, and she had been teaching Tai Chi in New York City for probably 20 years. She's still alive at the time of this interview, but she's really getting on it in age, probably in her 90s. So maybe that had something to do with it.

Jeremy Lesniak:

It sounds like it. When you put together, whether it's a new book or, one of these, these seminars, these events, you know, I think anybody who's trained can understand, you know, you're never going to be able to separate the training. You know, the training is part of your gymnastics training as part of your aikido, your system. It's all part of you. But you do have a choice as to what of that context for who you are goes into whatever it is you're bringing forward, whether a book or an event. And you've written a number of books and they come in at different angles, they bring in different elements of who you are and thus in my mind, different parts of your martial arts context will call it. How do you make that decision? Because let me add a Part B real quick, because your audience is not a martial arts specifically audience.

Dan Millman:

Yes, I do have quite a following, I believe. Over the years when I taught seminars, the number of people who've been involved with the martial arts, I think people involved in the martial arts may gravitate toward of a book called The Way of the Peaceful Warrior. Anything with the word warrior in it in the broader capacity of that struggle. I'm not sure whether you're asking me what moved me to write my various books…

Jeremy Lesniak:

No, it's not that, it's in the creative process. So this memoir, I mean, I'm going to guess the memoir starts with a kind of a big idea, macro idea, and then you decide how you're going to fill that in. So the ingredients, which how do you choose the martial arts ingredients?

Dan Millman:

At one point in my career, after writing about 15,16 books over like 35 years, I decided it was time to get back to writing and share what I learned about the art of writing. And so I wrote a first draft, showed it to my daughter, who I used to edit her papers. But then she passed me in terms of writing ability. And she said, “Dad, this is really meandering, this literary advice.” She said, “Let me take a crack” at it, and I said that would be great. We ended up publishing this book where it was published by a established publisher, but the book is called The Creative Compass, Writing Your Way from Inspiration to Publication. And she structured it around five universal stages of the creative process, and I hadn't really thought about it how it might apply to martial arts. But I know it applies to any creative art. And the five stages of creating a book a painting, a sculpture, a musical composition, and maybe even some innovative martial arts.

The first stage is dreaming. In other words, you come up with an idea, an approach, some innovation, but where it is in the life of the mind in the imagination. So that's the dreaming phase. And it has to start there.

Then the next step, the next phase is drafting. In writing, it's putting it down. It's bringing what was unmanifest into reality on a computer screen, on a page. And drafting is like muscular effort, just like laying a brick wall 100 miles long. Just one word, one sentence, one paragraph at a time.

And the next stage is the one most people skip. It's called development. Maybe you've heard in the movie making business, they call it Development Hell. It's when you step back and say, Is my creation? What was a castle in my mind right now kind of looks like a garden shed. And so I started to renovate and restructure, test it against reality. Is this what I wanted to express? And so that's what most people skip. They jump to the fourth level.

The fourth stage, which is refinement, polishing, refining it and so on.

And finally, of course, the sharing with other people teaching, learning, sharing, growing. And this probably happens in the development of any martial arts. Everything seems to go through these. We didn't make up these stages. My daughter knew about them, but she wrote them in this way. And then we structured the whole book around that. And each book goes through that process. An email that you want to compose carefully will go through that process. It's not just about writing, rewriting it, and you're done. So it goes through that whole idea of bringing it into the life in the mind and then manifest reality. I mean, how did people come up with various techniques and movements and counter movements? And it's it can be very, very creative. Obviously, Brazilian jujitsu is very much like that. I met a young man once named Josh Waitzkin, and maybe you recognize that name. But Josh, have you ever seen the movie Searching for Bobby Fischer?

Jeremy Lesniak:

I'm familiar with the movie. I've never seen it.

Dan Millman:

I highly recommend it. There is some of the best acting you'll ever see among five or six ensemble people. It's a touching, deep movie about a young chess prodigy and how he discovers chess and discovers he loves it and he's good at. The Queen's Gambit is a more recent and more popular kind of movie about chess. And again, chess, Brazilian jiu jitsu. It's all about strategy, right? And figuring things out. What's interesting about Josh is after he became one of the youngest grandmasters ever in chess, he took up push hands and he won the World Pushhands Championships in China against some not very fair play sometimes. But he won that championships, and then later on he took up BJJ. He opened a school with Marcella Garcia in New York City. And Josh has been doing that. I don't know what he's up to now, but he really was training. I went to see him roll, as they say in BJJ. and in that in a school in in New York City, where I now live. I haven't seen Josh in a while, but how many grandmasters in chess end up being world class martial artists? That's unusual,

Jeremy Lesniak:

I would imagine few, but I bet any of them could. It's a mindset.

Dan Millman:

It's a mindset. You're right. Absolutely.

Jeremy Lesniak::

Unpacking a puzzle?

Dan Millman:

Yes. Yes, it is. I don't know if I really responded to that, that question, but that's what came up.

Jeremy Lesniak:

That's OK. The questions are just to keep you talking. We don't have to go anywhere. I don't I don't have anything specific that we need to get through to call this a good or a success or done or anything like that. It's just it's us talking, it's us talking martial arts. And the beauty of the format is that everyone sees their relationship to martial arts and how it impacts their lives differently. And I like the variability of that because the people who are listening have different relationships to martial arts. Some of them are school owners. Some of them are dipping their toe in and went to their first class. Some of them haven't even started yet, but they feel an affinity for it and they want to, and they're hoping to get there soon. Yes, so too, to hear your stories is meaningful

Dan Millman:

Let me say something about I only referred briefly to studying the basic elements of kali, arnis, escrima, in order to teach a training I taught for 14 years, called the Courage Training, the Peaceful Warrior Courage Training, and it involved teaching the basic movements first. Five attacks in kali, first knife attacks, angular attacks, you know, level attacks and thrust and doing these movements with learning the movements. We worked a lot in slow motion. We emphasized deep relaxation while movement, and we got some amazing results. Now I could only take 40 people maximum and people came from all over the world to do this training, and it got a reputation of a certain kind. It was a three and a half three or four day training, an immersive training from before breakfast in the morning till bedtime at night in a retreat center in Northern California. I don't teach it anymore. It's so intensive. I needed a staff and it just got unwieldy after a while. But for 14 years, the people who showed up to this training, most were absolutely beginners in the martial arts. They'd never done a martial art before, but we got results. Well, actually, some of the people who came to the training were skilled martial artists, black belts. There was one fellow who was a seventh degree of black belt in taekwondo and another who had trained special forces and so on. They came not because they were going to learn new movements necessarily, but they were very curious about reported results we got from this training. Remember, the training was not to teach people to fight with knives or to become expert martial artists in four days. The training led to a test at the end of the training that was a culminating graduation ceremony some people passed the test, most did, some failed and those who failed to learn twice as much as those who passed. But it was about making fundamental shifts in their life, reflected in the way they faced the fear in the form of three attackers coming out of one at a time in rapid succession with steel knives. They were practice knives, they weren't sharp, but it was quite dry, mouth, high adrenal situational challenge. While the seventh degree black belt failed his test the first time. And it wasn't because he didn't have the physical skill or strength or stamina. He was a very good fighter, but he wasn't doing what we were looking for is flowing with life. He was the shift he needed to make was really relaxing and flowing with life, more being in relationship with us as we attacked. But he tested a second time, and he did beautifully, he made that shift. It's quite dramatic when that happens. Now the reason he took that training was to find out how we got the results we did. And what I mean by results is it's usually pretty much the equivalent of training six months to even a year in most martial arts in terms of being able to move instinctively without thinking. To trust the body to that degree where you don't think you know, one of my former mentors I describe in the in the memoir The Peaceful Hear Warrior Spirit, I call them the warrior priest. And he used to say combat like in life. If you start thinking too much, you're dead. And so they had to they were thinking and trying to figure out where we were going to come from next, it wouldn't work. They had to move absolutely instinctively and trust that. And that doesn't usually happen in four days. But it did in our training because of the slow motion we did. And because of the relaxation and drilling again and again, we told people that usually you're confused. I don't know what I'm doing. Then you do it right once. You go, OK, I'm bored. Let's move on. But we told them, No, that's just starting to get it. So we overtrained and people went through these confused places where they didn't know what they were doing or mentally confused, physically confused and yet if they persisted, they made a breakthrough. Let me share a story not about martial arts, but my 60th birthday. I wanted to do something different. So I ended up deciding I was going to learn to ride a unicycle. And I had a kind of a stiff back at the time, but nonetheless I wanted to learn to ride a unicycle. Now, I don't know, Jeremy, have you ever tried riding a unicycle?

Jeremy Lesniak:

Once and it did not go well.

Dan Millman:

OK, that's the universal response, and it's very humbling. Yeah, most people who tried it, it's just like, what? How do people do this? You know, I can ride a bike, but it's quite different. So a friend of mine loaned me his unicycle and told me to practice. He recommended a neighborhood tennis court in the morning because it's a good surface that I could get a death grip on the chain link fence, trying to ride around the perimeter on this unicycle, holding on. And at the end of every practice session and I was there alone, I just would leap forward and careen and see how many times I could pedal before it went out from under me. And I practiced for a week and I could get about six pedals before it went down. And then the second week, I actually think I got about almost 12 pedals, just like careening or not really riding. But by the end of the third week, I was able to ride figure eights around the tennis court. Now that I came back every day, the reason I'm relating the story and I think many martial artists are practitioners of anything will relate to this. I learned two things from learning to ride the unicycle. I relearned two things. First: Everything is difficult until it becomes easy. True in any physical goal, but the even more important principle, I learned was I confronted there were a couple of days in those three weeks where everything fell apart. There were horrible days. I couldn't do anything. I was worse than I was three or four days before that. Confused mentally, physically, but I came back and usually the day after those so-called bad days, I made a breakthrough. Sudden improvement and I realized that the learning was actually happening on those bad days. That's when the skill level was going from my front brain, my precognitive level to my back brain more instinctive. And I think that applies to martial arts for sure, and certainly did this knife fighting training. People are just going freaking out. I don't know what I'm doing. I can't. I can't even move anymore. I said, Stay with it, stay with it. And they made these breakthroughs and people amazed themselves. We couldn't predict who would pass and who wouldn't. It was one guy in Chinese tai chi shoes, was dressed all in black, perfect form. And we attacked him. He just stood there in place. And so we could never predict who was going to make a leap and rise to the occasion and who wasn't. So it revealed a lot about people. This is about self knowledge, not just about learning the fight with a knife, but it really is a metaphor. To me martial arts are a metaphor of how to live wisely and well.

Jeremy Lesniak:

I like it. Well, you've mentioned your book a couple of times, and it's coming out soon. And if I remember correctly as of when we're recording this…

Dan Millman:

Yes, when we're recording this, by the time it plays, I expect the book to be out. The official pub date is January 4th, 2022 – coming up in a couple of weeks.

Jeremy Lesniak:

I think this is scheduled for January 3rd, so I think this will, you know, for listeners who hit it the day of release - tomorrow.

Dan Millman:

Yeah, well, it's the book's officially published tomorrow. It'll be up on all the platforms and I'm not here like to promote the book because it may or may not be of interest…

Jeremy Lesniak:

Well tell people about it so they can get a sense as to whether or not they want to investigate.

Dan Millman:

Sure. The subtitle of the book Peaceful Heart Warrior Spirit is the true story of my spiritual quest, and I believe we're all on a spiritual quest. Whether or not we might use that term or recognize it consciously, who isn't looking for a deeper sense of meaning and connection and purpose, a sense we count for something asking, You know, where do I fit in life? What is it for? Maybe we don't think about that all the time. We're too busy with the conventional things in everyday life as we ought to be: kids, education, training, work, and so on, making a living. But there are times we wonder about these questions.

So I would not presume to write a book just about me, assuming everyone wants to read about Dan Millman, especially if they haven't heard of me. But many people might be interested in this idea of a quest, and it's a bit of a cautionary tale. It offers guidance. I take people along for the ride of the four primary mentors I worked with over 20 years and one I call the professor, one I call the guru. I was with that person almost eight years on and off. One, the warrior priest who is a martial arts instructor and a better physician. Amazing guy and the fourth I called the Sage. And they represent different aspects to the search for enlightenment, illumination, peace, liberation, the transcendent search. So it's been said many ways. In search of the miraculous. You know, so I think that's what we're really looking for when we trained in the martial art do a sport or we pursue any endeavor. Maybe we're a physicist. We're looking for the edges of reality where reality meets a little bit of magic. And that was the larger quest. You know, I began my career kind of searching for ways to create more talent for sport. When I was an athlete and then a coach, I asked myself. Well is talent innate or can it be developed? And I defined talent. Jeremy has the ability to learn faster and easier and higher potential rise to higher levels. That seemed like a good definition of talent, and it seemed to me that talent was about 20 percent innate - certain body types. Physical characteristics. Psychological characteristics might lead one to some innate talent inborn born into the right stars, whatever. But it seemed to me that about 80 percent of talent for sports could be developed.

And I asked myself if it could be developed: What qualities do you need to learn faster and easier and rise to higher levels? Well, strength, obviously. Muscular control, even if you're a violinist, you need muscular control. And suppleness range of motion, proper posture and range of motion and then stamina to be able to train and so on. But I think the most important was sensitivity. Elements like coordination, rhythm, timing, balance, reflex speed. So and of course, the master key to all these is the ability to relax in motion.

So my theory is it turned out worked well in practice. When freshmen came to train in gymnastics with me at Stanford instead of focusing on new skills in gymnastics, we focused on that foundation of talent. All those qualities and the theories did bear out in practice. The team went from the bottom of their conference when I began coaching them to one of the top three teams in the nation, and as I mentioned. I trained the top U.S. Olympians as well. And I might still be coaching today, but that's when I realized that being able to do somersaults and cartwheels and handstands, those skills themselves didn't really help me when I went out on a date. You know, they didn't help me when I got married or had children or dealt with financial questions or career decisions, the things of everyday life. So that's when I made that fundamental shift. And I started asking bigger questions, how can we develop talent not for sport or martial arts, if you will, but talent for living? What qualities, what skill sets weren’t we taught at school and that led to, well, a lifelong search, the quest for illumination. Or just say life skills. And it took me around the world and eventually led me to these four rather unusual mentors who represent radically different people who represent different aspects of this bigger searching life. The spiritual search. So that's how I made that transition to what I do now. And the memoir Peaceful Hear, Warrior Spirit is about the foundational elements of my life that led up to and prepared me for these teachers. It's my life as a young athlete in the martial arts that led to a sort of a larger spiritual education is nothing to do with religion or beliefs. It was more of a psychophysical training and quite intense that I'm finally able to share in the full context in the new book.

Jeremy Lesniak:

One of the things I appreciate about what you just said the number of books of yours that I've read and I guess really the way life unfolds is it has to happen in its own time. You talked about these four mentors and. They couldn't have come in a different order, they wouldn't have been the same, they wouldn't have had the same lessons, you wouldn't be the same person. And I think so often we look at where we've been and it can be really easy to point to something is as specific as I could have been better at yesterday's class, yesterday's training, I could have done more at this competition. I wish I had started my martial arts career with this art or this instructor or or. And yet if you had done it any other way, you wouldn't be where you are. And that's what I'm hearing,

Dan Millman:

That's extremely wise, and I hope you keep that on the program because that's a major contribution. In fact, when I'm asked, what do you want people to take away from your new book, Dan? It's that sense of self trust, trusting ourselves and our process. And it's not comparing ourselves to other people because as soon as we compare ourselves to someone else, we're even going to feel superior or inferior. And it's a profound disrespect for our own way of learning and living, our own process, our uniqueness because each of us has a story and it's like no other on the planet in the details of that story. You know when I was training in gymnastics and teaching, I noticed that some people are somersaults faster than other people. But those who took more time to learn it often learned it better than those who learned it quickly. Yeah, I think it was that Lord Chesterfield, who once said I cannot write a book commensurate to Shakespeare, but I can write a book by me. And so I think overall, in the experiences I share in this book, I hope people will come to a greater sense of perspective and appreciation for their own life and process. And you are quite right that I couldn't have met these mentors in a different order. It wouldn't have made any sense. So yes one thing prepared me for the next, and my failures prepared me for the successes. And that's what I mean by trusting the process.

Jeremy Lesniak:

You mentioned, but say it again, please, where can people find this book?

Dan Millman:

The book is published everywhere on all the platforms, Amazon, Barnes and Noble, online bookstores, and it's in stores as well, but more reliably know it's easier to get online. Also, there's an audio version, I recorded the audio book. And also, it's an e-book, of course, it's out there for the Kindle over the Nook or an iPad. Whatever e-readers people have is awesome.

Jeremy Lesniak:

I hope people will check it out. I'll be checking it out. And we always end the show as the guest wants to. So this is your chance to talk to the however many martial artists are listening right now. What final words do you want to send them away with?

Dan Millman:

Well, first of all, anybody who is training in the martial arts, I want to congratulate you because based on my experience, it could be a tremendously positive experience, but it will teach you about self trust. If there is a perturbation, if there's problems, don't be shy about exploring different teachers. Don't feel locked in. Martial arts is not a religion. It's a practice and explore different arts, try different arts, even if you're committed to one. I go to a seminar and another hour just to explore and see how it enriches your perspective on the art that you've chosen. And again, no best art, just the best for you at a given time of life, so that can change over time as well. But I do congratulate you. I feel like a kindred spirit. And anyone who studied the martial arts or any form of movement. So my heart goes out to you.