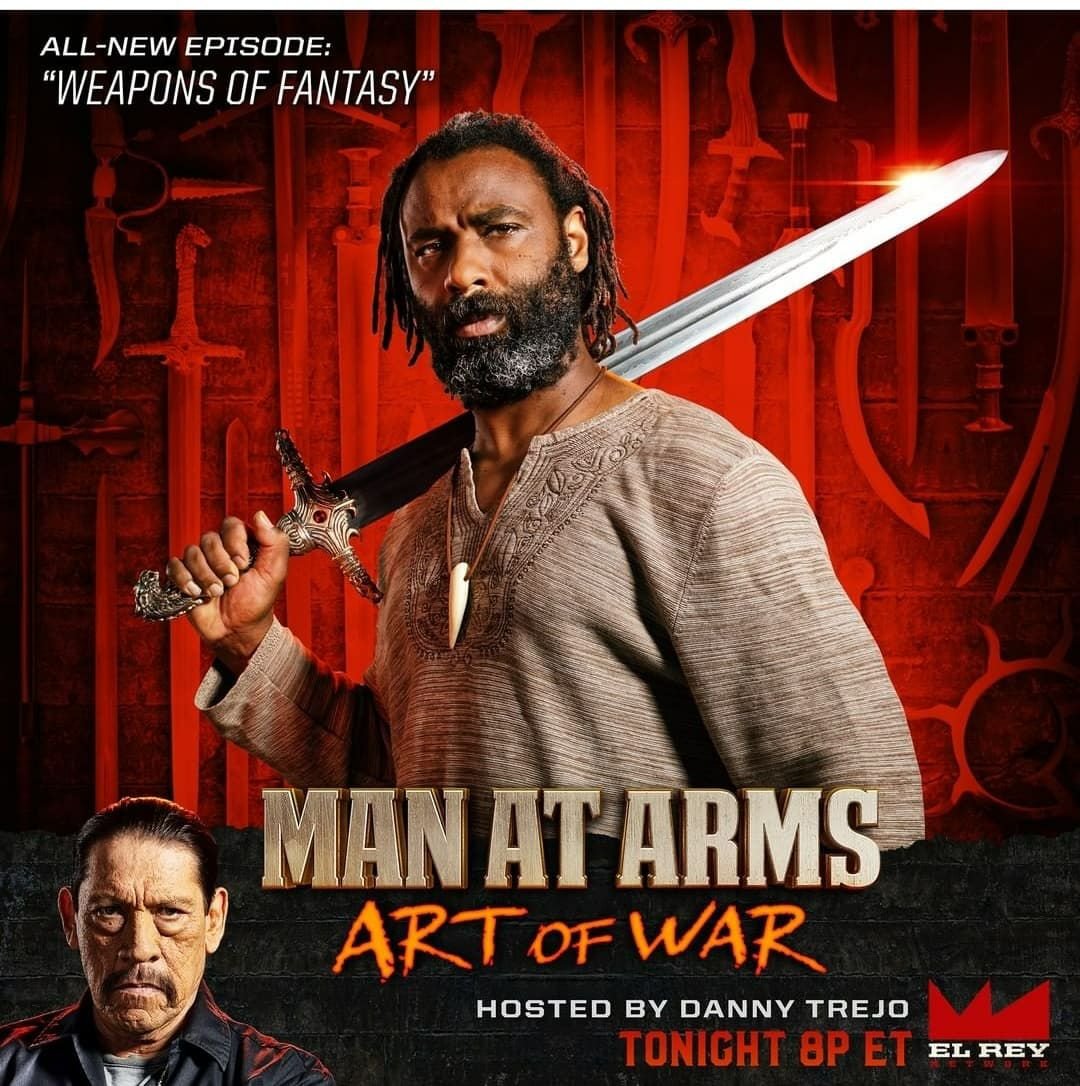

Episode 822 - Mr. Da'Mon Stith

Mr. Da'Mon Stith is a martial arts practitioner, instructor, and president of Historical African Martial Arts Association.

I knew that I wanted to be a Martial Arts instructor. I didn't know how I was gonna get there, you know? Because I had just stepped away from the class. But at that point in time I knew that was something that I wanted to do.

Mr. Da'Mon Stith - Episode 822

Martial arts practices vary across the globe, each country contributing its unique style. While popular Asian martial arts are widely known and celebrated, African martial arts remain relatively obscure. President of the Historical African Martial Arts Association, Mr. Da’Mon Stith has dedicated his passion to the exploration and preservation of African martial arts. Mr. Stith’s interest in African martial arts was sparked when he discovered that such practices existed and were not well-known.

Mr. Stith’s interest in martial arts began at the age of six, when his father gifted him a toy sword. As a child, he would watch martial arts movies and then reenact them with other kids in his neighborhood. However, due to asthma, he turned to martial arts after playing football. From toy sword, Mr. Stith is the Chief Instructor and Founder of Guild of the Silent Sword.

In this episode, Mr. Da’Mon Stith provides insights into his journey of exploring martial arts and his desire to learn more about the cultural and historical significance of African martial arts. He highlights the importance of community and collaboration in martial arts and emphasizes the need to support and learn from each other. Tune in to learn more about his passion for African martial arts.

Show notes

You may check out more about Mr. Da'Mon Stith:

www.hamaassociation.wordpress.com

www.youtube.com/c/DaMonStith

www.instagram.com/damonstith/

This episode is sponsored by Kataaro.com

Show Transcript

Jeremy Lesniak:

Hey, what's happening everybody? Welcome. This is whistlekick Martial Arts Radio, Episode 822 with my guest today, Da'Mon Stith. I'm Jeremy Lesniak. I host Martial Arts Radio. I've founded whistlekick and I love traditional martial arts. Been training my whole life, and I bet you also love your training and that's why you're here. We come together as martial artists in a number of ways. This show being one of them. What are some of the other ways, some of the events, the trainings, the things that we do? Go to whistlekick.com, check 'em out. Use the code podcast15 to save 15% on just about anything over there. We got some cool stuff and it's constantly changing. Now, whistlekickmartialartsradio.com has all the stuff for the show, all the show notes, all the transcripts, all the links, all that good stuff for this and every episode we have ever done. So you can consider checking that out if you like what we do, if our mission to connect, educate, and entertain, resonates for you. If our goal of getting everyone in the world to train for just six months means something to you, please consider supporting us. There are a few things that you can do. You can join the Patreon, patreon.com/whistlekick. You can leave reviews, you can buy books, you can come to events, tell friends, all great stuff. But here's another thing you can do. You can support our sponsors. Today's episode is brought to you by Kataaro, and if you know Kataaro, you probably know them for making the best martial arts belts in the world. In fact, the word Kataaro means weaver. Did you know that? Kind of cool. And their mission is very similar to ours, but in a different way to provide extraordinary service that creates a memorable experience. It honors each martial artist's journey. If you watch me looking off-screen, I wanted to make sure I got that right. And if you use the code WK10, capital W, capital K, numbers one zero, and get 10% off your first order at Kataaro, all their stuff's handmade in the USA and I think that that's really, really cool. I've got a Kataaro belt. I like it. It is an amazing belt. And there are two categories of you out there. You either know what Kataaro does, you've experienced their quality, and you're nodding along with me right now, or you don't know about Kataaro. So I wanna urge you. Go to Kataaro.com, K A T A A, two A's R O, that's kataaro.com, and check out everything they've got. Use the code WK10 capital letters to save 10% on your first order. Today's episode is with Da'Mon Stith, and as with many of our episodes, there are common threats with other episodes, other guests, other stories. There's a point in here where it takes a rather hard left as Da'Mon talks about wanting to shed a light, bring experience to, and understand himself, something that is not discussed in the martial arts world, at least very little. And he's had a large share in improving that conversation. African Martial Arts. So we're gonna talk about his journey and how he got to the point where he could start doing this work on historical African Martial Arts, and it's absolutely fascinating. I'm sure you'll enjoy it. Here we go. Hey, Da'Mon. Welcome. Thanks for being here.

Da'Mon Stith:

It's my honor. Thank you for having me.

Jeremy Lesniak:

Yeah, I appreciate it. Well, you know, I was checking out some of your YouTube videos beforehand, and actually, in part because I wanted to make sure I got this, the pronunciation of your name right now, we don't get too many people on that have an apostrophe in their name.

Da'Mon Stith:

Yes.

Jeremy Lesniak:

And you know names, right? Like…

Da'Mon Stith:

Yeah, yeah.

Jeremy Lesniak:

Try to get names right.

Da'Mon Stith:

Yeah. The apostrophe is important. It's kinda like the fancy characters, like the fancy names, like the apostrophe, you know, accent it and make it,

Jeremy Lesniak:

You're throwing me back to like, when I used to read Anne McCaffrey stuff. Do you

Da'Mon Stith:

Yeah.

Jeremy Lesniak:

Do you remember those books, the Pern books and when they became a Dragon writer, their name became a contraction?

Da'Mon Stith:

Yeah, That's so…

Jeremy Lesniak:

So you ride dragons? That's really all we have to say.

Da'Mon Stith:

Yeah. Dragon born.

Jeremy Lesniak:

You know, we're gonna talk about you and your story here and a little bit of foreshadowing my gut tells me that we're gonna end up in some directions. We haven't gone often, perhaps ever on this show, and that excites me. But let's roll the tape back to the beginning. It's a martial arts show, you're a martial artist, we're here to talk about martial arts. What was your first experience with martial arts?

Da'Mon Stith:

Oh, well I mean, it was a dark and stormy night and my father gave me the gift, the gift of a sword. That's usually how the story goes. I was six years old and my dad showed up with two gifts. Giving you a different answer to this one. I normally, I answer just with the sword. He gave me a sword, a toy sword, and a toy gun. And mind you, you can see all the gray and white in my beard. This is like the eighties where it was like, you know, that was a thing and all that kinda stuff. So it was almost like if you have seen Shogun Assassin the long walking cops series where he's the father is like gonna take the road vengeance. And he on a choice, like, you know, choose the sword or choose the ball and you'll join your mother, choose the sword and you'll come with me as you walk, you know, the road to hell and revenge. So like, in that moment for me, I gravitated towards the sword. And it was like, you know, looking back at it, it was like this, it was like a, just this cheap lead-filled silvery, it was like, it was a silver, it had a silvery hill, silver scabbard with like cheap plastic jewels purple with reefs and greens.. And the blade was like black. And I was just like, I just loved it, you know what I'm saying? It's like I played with it into like completely fell apart.

Jeremy Lesniak:

Yeah.

Da'Mon Stith:

And then like salvaged as much of it as I could. And just like it, it left this impression in me, like after I had lost it, it was all said and done. When it was gone, it just left this like this hunger, this curiosity in me that I was looking for things, you know, I was looking for more things about weapons and about warriors and about, you know, just the story of people standing up against, you know, impossible odds. And, you know, I found a lot of, what is the word? I guess I found that in media at the time, you know, watching movies. So a lot of like, of course, Kung Fu movies from like the ‘70s and ‘80s watching some of the peplum, the sword and sandal movies, and stuff. Like Clash of the Titans and of course, Excalibur was like a big thing in my, a big in my rotation. But does anything that had to do with like, you know, warriors, warrior culture, fighting the good fights, standing against impossible odds, like that was where like my heart was like, you know, really, really connected with that. So the way it worked for me, cause martial arts was a thing that a lot of us growing up in my neighborhood. We didn't really have access to in the same way where there weren't like lots of dojos around. At that time what was considered a martial art was very, very small category out of, you know, at the body of like.

Jeremy Lesniak:

Sure.

Da'Mon Stith:

Combat tradition that we have today. It's like, you know, martial arts is a worldwide thing and it has different faces from combat sports to war dances to, you know, this all-embracing large tree with several branches of different manifestations of warrior traditions. And so at the time, like martial arts was very defined primarily as like East Asian combat traditions that were practiced, you know, in the United States or wherever else. So Karate, Kung Fu, Aikido you know, I think like Aikido and Judo was like exotic stuff. Karate was like, you know, a little bit more like accessible. But, so anyways, as a kid there weren't any studios around. So like the way we, the way I practiced my introduction and where I got my feet wet and it was like we would watch the movies. And then we would go outside and we would reenact the movies.

Jeremy Lesniak:

And you're certainly not alone. We've had quite a few people on the show, but for whom that was the first few years.

Da'Mon Stith:

Yeah. And so by doing that, it kind of instilled this idea of like martial arts as you know, of course, it's like training you how to fight and how to be badass or whatever else. But it was also like about being able to tell stories and about like personal expression. Like you can express who you are, you know, through these movements and through how you fought. And that was something that really stuck with me as a kid.

Jeremy Lesniak:

That, and just going on my gut here, talking about the way that your father kind of gave you this choice. And then, you know, going on and finding some passion for protector-hero types. You know, if this was a therapist's office, you know, they'd look at that and say, you know, did you, you know, did you feel like you had to be the protector?

Da'Mon Stith:

Oh yeah. Big time.

Jeremy Lesniak:

At a young age, you know? And it, can you speak to that a bit because it sounds like it really informed your martial arts destiny?

Da'Mon Stith:

Most definitely. So I'm the youngest. My brother and my sister, they are 10, 10 years older than me. They've passed away now, so rest in peace.

Jeremy Lesniak:

I'm sorry.

Da'Mon Stith:

Yeah. I appreciate that. So they're 10 years older than me. My mom, she met my father and they were married briefly, and then they separated when I was young. So my mom was a very beautiful woman. Very vibrant woman. And I, as a kid, I always felt like it was like my duty to like be her shield. And to like, protect her. So like any, I was a kid, like, if you tried to date my mom, I'd be the kid. That'd make it really, really difficult for you to get any progress, you know? Sometimes, you know, it was through my antics. Other times it was through me, like, you know, being very, very directly saying, this is, you know, no, this is my mom. Like, no, not at all. So yeah, maybe he hear him in the back, he call me a sucker but on the other end of that, also being the youngest kid and then doing things like in the '80s, you know, in a lot of ways we were like left to kind of problem solve interpersonal stuff on our own right. So that dealt that, you know, meant, you know, conflict with, very seldomly just with words. It meant like having to fight a lot. So I was really quiet, reserved kid, and I couldn't always call my big brother was this, you know, he was an all-around athlete, big, strong guy, looked like a wrestler to me. In my mind as a child, it reminds me like kinda larger than life, really big, strong guy. But I can never really only in some very, very severe cases would I ever call him to like, help me out in a situation. I typically, basically had to kinda fend for myself. And so like martial arts was like my armor. Being even just like watching the movies and going outside and adapting that into like what I did. It gave me like a different dimension than my you know, the kids that were in my same neighborhood who probably weren't getting those kinds of influence and, you know, like yeah, I wanted to be, I felt the need to have to like, one to protect myself, to be able to like, cause you know like I said, I'm was quiet, very reserved, very soft-spoken. And usually, those are the kids that end up and I was a loner. And usually, those are the kids that, you know, get targeted and so yeah, I wouldn't start fights. I wouldn't cause trouble. I definitely would fight when the situation arose. I didn't win all my fights, but I definitely you know, showed up for them. And martial arts and just the mythology of the warrior helped me to like to do that.

Jeremy Lesniak:

Thank you for sharing that.

Da'Mon Stith:

Of course.

Jeremy Lesniak:

So where does your journey take you from there?

Da'Mon Stith:

Ok, so formally, it takes me to football.

Jeremy Lesniak:

Ok.

Da'Mon Stith:

Football, asthmatic skinny.

Jeremy Lesniak:

Where'd you grow up?

Da'Mon Stith:

Where I grew up? Yeah. Let's start there. So, grew up in Austin, Texas.

Jeremy Lesniak:

Ok so football, you almost didn't have a choice, right? Football culture there is so prevalent.

Da'Mon Stith:

It is. My brother was a football player. He was a football player, a TrackStar baseball, an outdoorsman, artist, he was all those things. My stepfather was military, so we lived in Austin for a bit and then we moved, we kinda bounced around to different states in different cities. So we had moved when I went to my next phase in my martial arts training happened when we were stationed, he was stationed in Panama City, Florida. And so I wanted to like impress him and I was like, well, the football players, they wear armor. And I'm like, I can go be a football player and then, you know, kinda do this thing. So I went out, I tried out for the youth center football team, the Tyndall Falcons and I made the team and I'm doing the thing, but you know, the only problem is like I have this disease that didn't exist back in the eighties called asthma, right? And so, sorry.

Jeremy Lesniak:

It's ok.

Da'Mon Stith:

So yeah, so I had asthma. It made it very difficult for me to like, keep up with all the running. And my coach was very, you know, ill-prepared to like teach breathing exercises, even just to be sensitive. That kinda stuff. You know, like my coach was like the stereotypical eighties football coach, you know, like handlebar mustache, he wore like a cap with the mesh bag. He wore shades, the tight shorts, you know what I'm saying, the shirt tucked in there. And he just you know real clipboard for no reason. Damn, it's harsh. But you know, so I started to I was having asthma attacks after training and I started lying and skipping out on practice and my dad would like ask like, what, you know, like, you know, well, what'd you do today? Like, what you guys learn? Like what's your, what you gotta work on? I would make up stuff like, yeah, you know, I'm gotta go and work this and do that. And, you know, it got to a point where we were getting our positions for the team, like where, what roles we're gonna serve, my dad asked and I'm like, yeah, I'm gonna be a wide receiver. I didn't to this day, I dunno what a wide receiver does. I didn't know back then. I just knew that a wide receiver was something important and so, you know I told him that I was lying and it eventually caught up to me, my dad and the coach, my parents, and my coach had a conference, ended up that I was actually not going be a wide receiver. I was gonna be at tight end. I still dunno what the heck a tight end does to this day. But again, it was the eighties, instead of them like signing me out of football, they said, hey, pack your stuff up. Go walk down there and tell the coach that you're quitting. And I'm nine years old at this time, eight, maybe eight at this time. And I go to this guy and I'm like, hey, you know, he's like, everyone's like, I can, I still see it today. Like everyone's already out in the field. I'm late. He has this, like, he has his thing in his hat. He's like doing his thing and walks. I walk up to him, I got the shoulder pad, the helmet through the shoulder pad some. I'm doing a walk of shame. And he's like Stith get dressed out, and I'm like sorry, coach. I can't, what do you mean? And I explained to him that I have this breathing illness called asthma. And he proceeds to like, you know question my manhood and my tenacity calling me a bunch of things I won't say right now. And I walked off the field. I was like, very, very embarrassed. I felt, you know, already again a very soft-spoken kid. A very reserved kid, you know, and struggling with this idea of like what masculinity is and stuff. So I'm walking off the field, going back to my bike, and it's feeling like, you know, feeling, you know, not really good about it. And so I'm driving past, I'm pedaling past the youth center, and I remember there's this guy in the youth center, his name is Sonny. And Sonny was a break dancer. He was a breaker and he was a martial artist. And I remember him doing like seeing him break and seeing him do like these crescent kicks in the rec center. And I was like, you know, they have a karate class at the rec center. I should just go and, you know, sign up. So I went to the youth center, got the paperwork for the karate class, and I took it to my mom and told her that I wanted to do it. My stepfather was like, you know, and then martial arts was very, mystical at this time as well, right? And so my stepfather was like, yeah, you don't have the discipline to do this. You know, blah, blah, blah. You know, it's like, this takes a lot of, you know, all this stuff. And, you know, so it was kind of put on hold for a bit. And then he went to a TDY, which is like a, it's temporary active duty. So it's like when you're stationed one spot, then you go to another spot for a couple of months or whatever else. So when he went TDY, I went ahead and signed myself up for the karate class. So when he came back, I was already in the class. So I started doing a, it was an Okinawan style. I'm not sure if it was but it was an Okinawan system. My sensei, I think his name was Don. He was super like, super geeked out when the karate kid came out, this is, I'm dating myself. Like he was excited. Like, yo man, they were doing, they did the crane kick, the crane stance. It was very similar to our cat stance. And he was like relaying all of this stuff about it. So really, really hype. This is about 80 you know, 85, right? So I did that. I started doing karate, but I, to be honest, my dad was sorta right. I was not ready for the discipline in that sense. I wanted to like punch and kick and flip. I didn't wanna do kata. I didn't wanna do any of those things. So I started training there for a bit and then, gosh, I broke and ended up breaking my toes. Unrelated stuff. Stupid.

Jeremy Lesniak:

Ok.

Da'Mon Stith:

I used to be a breaker too when I was a kid, so I broke my toe doing that. And so I was out for a little bit and then I came back and then when I came back we had, the class had grown from like a really small, maybe like five to seven people. And we were in like the small, the rec center room. Gosh, when I came back to class, it was like that scene from Enter the Dragon where it was like everybody's all punching in unison and doing this. Yeah. Yeah. And I was like, oh wow, this is, it's different.

Jeremy Lesniak:

Class had grown.

Da'Mon Stith:

Yeah, it had, and I had grown too. I had grown in ways where I was the kid kind of like Jackie Chan a little bit, where when everyone is kind of doing what the instructors tell 'em to do, I'm over there making up my own moves and, you know, doing it by, you know, doing that kinda stuff. So eventually we had to, you know, part ways in that sense so.

Jeremy Lesniak:

But it sounds like you started to find some things within martial arts in a class setting that resonated for you. It sounds like it's the stuff that you saw in the movies, the stuff that worked or at least helped you when, you know, things escalated beyond words and you're like, ok, I see something here. That's kind of what I'm piecing together.

Da'Mon Stith:

Yeah, and I definitely, like, from that age, from nine I knew that I wanted to be a martial arts instructor. I didn't know how I was gonna get there, you know? Cause like I said, I had just kinda, I had just stepped away from the class. But at that point in time I knew that that was something that I wanted to do. Like even whatever, what I learned. I would share those things. Like I didn't just do it in class like I took it home with me. I shared what we were learning, what I was learning with my friends just because, I don't know, I felt something in, I felt it made me feel good to do that. Something motivated me to do that. And I and I've known since I was nine, like, this is what I wanna do. I just didn't always know how I would go about doing it or, you know, what opportunities would present themselves.

Jeremy Lesniak:

So here you are nine years old, you're not training anymore, but you wanna be a martial arts instructor.

Da'Mon Stith:

Yes. And I am living it and this is like, and I'm, this is my path, right?

Jeremy Lesniak:

Yeah.

Da'Mon Stith:

And this is not necessarily the path where everybody but this was my path. And so like, yeah, I stopped my formal training at that point in time. And I just played, it just was, it was a part of me, and like I played

Jeremy Lesniak:

What did that look like?

Da'Mon Stith:

That looked like I think for most kids that don't like grow up in a culture where they have to be physical in that way, you have to teach them how to like punch, how to swing a stick, maybe how to kick. But when you play at it, we're doing it. So we're doing it so much that it's like, and there's no one it's like, it's when you watch children play, they play with this like intensity completely enveloped in this world, right? Create this world and they're completely enveloped in this world. And you don't put it down. It becomes like part of your DNA. And so for me, Is like, my identity as Da'Mon and as a martial artist became fused as like one, so like, you know I would punch, kick, flip, sling a stick go through these adventures, whether it was with my friends or by myself. I just played with the movements and it wasn't always a very conscious thing. It was just something that was like just a form of breathing for me in a sense.

Jeremy Lesniak:

The way you're talking about this reminds me of breaking culture in the eighties.

Da'Mon Stith:

Yeah.

Jeremy Lesniak:

That you took that kind of methodology and applied it to combat.

Da'Mon Stith:

Yeah. That is exactly it was very, very, and to expand it out, just like hip hop is like, that's kind of like the idea is like, You know you develop, you test yourself, you develop your style, you develop your expression of it. And it, for those days it was just like play. Eventually, I had the when eventually my next, our, we moved back to Texas and then eventually moved to Okinawa, Japan. And so when I got there, that was like the next like transition transformation for me.

Jeremy Lesniak:

How old were you when you made it to Okinawa?

Da'Mon Stith:

I was 13.

Jeremy Lesniak:

Ok.

Da'Mon Stith:

13.

Jeremy Lesniak:

So a few years later. But I would imagine the perfect age.

Da'Mon Stith:

Oh yeah.

Jeremy Lesniak:

A boy who's in love with martial arts and has been kind of making a go of it on his own and now you're in. You know, would some consider one of the hotbeds?

Da'Mon Stith:

Yeah, most definitely. And that's what I felt like when I was there, like the total culture shock, like when you step off the plane and it is like everything is different from what you've experienced and what you've known, the sights, the sounds, the people, the writing, the energy, you know what I'm saying? I live, I was fortunate. I'm really glad, I was fortunate to live off base for about a year before we moved on base. Like living off base was like wonderful. It was in my head again and I'm coming from a place of like not just an activity or a sport. But like a world, you know what I'm saying? So like, I'm actually seeing stuff that I've seen like in the movies, even though there's different places. And in my young mind, I'm seeing it as the same thing, but like, I'm actually feeling like I'm like, there. So yeah. So it was like immersive in a lot of ways. My father, well, they only have like one at the time. They may have, this may have changed. They only had like one like American like television channel out there and it was, you know, not really good. We got things probably about a month behind everybody else or so. So like a lot of families had these really, really extensive like VHS movie collections. Right. And that was a big business out there. It's like, you can go, you can purchase like you know, movies and stuff from shops and things. So my dad actually went to, he was there about a year and a half before we actually came and joined him. So he had this extensive collection of all these movies, like action movies, movies I would watch on Comfort Theater, you know what I'm saying? All this stuff. It's like endless. And so like, I was just like in it, like, just like in it. That's why I would watch the movies and then like, I would like run around and walk around my neighborhood and just like be there. Like it was yeah, it was just, was immersive in that sense. So yeah. At that point in time, I'm sorry, I'm just rambling on…

Jeremy Lesniak:

No, no, keep going. Keep going.

Da'Mon Stith:

Yeah. So, you know, I'm 13, I'm at the height of puberty. You know, I look funny, sound funny, I'm in a new place. And of course, you know, I'm raised basically by like, action movies. So I, my interpersonal skills is like, well, yeah, you know, hey, clearly I'm the good guy. There's the girl and then there's the bad guy, you know? So it's like really simple. So I'm thinking that ladies like can do really high jump kicks or random katas for no dang reason, you know.

Jeremy Lesniak:

If only that had been true, I would've been much more popular in high school.

Da'Mon Stith:

Yeah. No. But so eh, gosh, in seventh grade I spent a lot of time this being like a kinda a weird martial arts nerd. And eighth grade I decided like, hey, I'm gonna be a normal kid. I'm gonna like finally get a girlfriend and just be normal. Stop doing martial arts and just be normal.

Jeremy Lesniak:

Had anyone encouraged you to do that or did you come to that conclusion yourself?

Da'Mon Stith:

I came to that conclusion myself. Right. And, you know, hey, I'm a normal kid. Eighth grade, I got a girlfriend, great. Holding her books, walking her around, all this kind of stuff. But only problem is that, you know, she has a boyfriend, an ex-boyfriend who is not quite over her, and he has like lots of friends. And you know, there was a potential that he was like, you know, gonna, they were gonna jump on me. And so like, man, I was I learned about this and I was like, wow, man. You know, I was really trying to like montage myself into like, Fighting preparedness and just kind of realizing that yeah, I couldn't do that. Fortunately, nothing really came of it, but it did like awaken this need of like, yeah, I need to get back into some type of training, not just, and I, at that time, I wasn't even like playing at it. It was just like I wasn't anything. So I went to the USO on Camp Foster as a marine base, and I signed myself for the [00:29:58] classes taught by Isao Kise, excuse me, he's the son of Fusei Kise, Okinawa and so like, yeah, I began training Okinawan Shorin Ryu Karate with him. And in that point in time I was like you know what I wanna try and be very serious in my like approach and in my, I'm gonna learn kata, I'm gonna just kinda go through and force myself to like, embrace these other aspects that I didn't feel like I was interested in at the time. And so…

Jeremy Lesniak:

Yeah go ahead, keep going. How did it go? Keep going.

Da'Mon Stith:

It was great. You know, like I was growing, I was getting stronger, getting more confident. I mean, I was like, I was Miguel Diaz in Cobra Kai in a sense, you know, that was kinda me. Rose pretty quickly through the ranks. And then like I kinda hit this wall so a year, I go back a year before, like back when I was just kinda playing around or whatever. I had come across the book, Miyamoto Musashi's book of Go Rin no Sho. And I read that and it had like this really, it had this like profound effect on me when I first read, I was looking for Lord of the Rings right? I was doing like a, the card catalog search at the Air Force Library. And then I came across Book of The Five Rings. I thought it was connected in some way. I found like it had like old school one with the, where it's holding two wooden [00:31:32]. This is not Lord of the Ring, but this is probably cooler. So I got it and I read it and it was like I didn't understand everything that I was reading. But it was hitting me in certain ways so fast forward about a year later, I stopped training and then I started back training and I'm kinda growing in this art. And so I read this article, it was like a comparison between the philosophies of Miyamoto Musashi and the philosophies of Bruce Lee. And when I was in, when I read that article and I was introduced to Bruce Lee's art, it kinda, it, both of them had changed me how I viewed martial arts at the time. For one, seeing the way in all ways as the, as a fighter martial artist, swordsmen or whatever. Seeing the way that practice in all things you do. Was something that really spoke to me. Especially like not always having access to formal training. I had to train in a way that was very immersive. Also, you know a fighter should be not just skilled in the arts of war, but also should be skilled in the arts of poetry, calligraphy, tea ceremony, other activities, cultural activities or that add this type of balance too, you know, the other training. And so I saw martial arts as a form of like, expression, like an artistic expression as well. Then coming across Bruce Lee's philosophies of martial arts, not just being like an expression of an art, but also being expression of you, like a personal expression of you. And that not we were not, we're the same, but we're not all the same. We have different attributes, different mentalities, and different ways and approaches to like fighting and using fighting as a way of, as a medium for expression. We have different ways of going about that. And there are different arts that add different elements to achieving those goals. And that kind, like I know like a lot of martial artists, like, well, not everybody's Bruce Lee can't create your own style and you can't do, this can't do that. And I didn't really have anyone to tell me that I couldn't do it. So I was, it planted this seed in me that like I wanted, and the karate training was great. You know what I'm saying, but like I wanted more, I needed more. From what I was getting. And it wasn't, like I said, a deficiency from what I was learning. It's just like there's more out there like I wanna experience more. So I started to slowly dial back in my karate training and started to explore Jeet Kune Do and that led me from, so I'm in eighth grade going into ninth grade. I think by the time I got into ninth grade, I had fully like I'm kinda more applying and adding into some of these JKD concepts into my training. And then I'm, and by ninth grade, I stopped training Shōrin-ryū. Independently training. With JKD and you know whatever else and that became like my, and again, my high school time period. There's always this like ebb and flow of like intense training and then like, ok, well I kind of like to have a social life and be not so crazy. So then I kind of dial back and then there's something that comes that's like, oh, ok, well, you know, you gotta deal with conflict. Not necessarily dealing with conflict always with your fist, but you gotta at least have something that helps you to stand up and face challenges, you know? Not always just about punching or kicking someone, but having the ability to do some things or having the, having being familiar with being uncomfortable helps you in like dealing with someone in your face or dealing with someone who has a disagreement with you or wants to punch you in your face because you're inoculated to that in a sense, and I in many aspects in my high school time. I had stopped training and then I had to start back. But finally, it was kinda like a back-and-forth through high school. It was always like part of my identity, but it wasn't always something. I was very intensely training like probably until junior year where I had like a breakthrough and it was like, yeah, I'm like I'm full in now and that was kinda what led me to kinda where I'm at now.

Jeremy Lesniak:

Ok. And, well, where is that? I know we'll go back and we'll fill in some gaps, but you kind of set me up for that question, so I'll ask it.

Da'Mon Stith:

Well, so now where I'm at currently is I am researching and reconstructing historical African Martial Arts. And that is like, A culmination of my life trying to figure myself out as a martial artist and as a person of African descent living in the United States. Nice.

Jeremy Lesniak:

Wow.

Da'Mon Stith:

I'm sorry. Also as a swordsman.

Jeremy Lesniak:

And you still love swords.

Da'Mon Stith:

Still love swords, yeah.

Jeremy Lesniak:

You made that.

Da'Mon Stith:

Actually, my business partner made it.

Jeremy Lesniak:

Ok.

Da'Mon Stith:

This is what we do, we make swords. That's a whole other story as well. We'll get into that.

Jeremy Lesniak:

Yeah. We'll get there.

Da'Mon Stith:

So yeah, so like it's this culmination of these two parts of me that have come together. My love for history was birthed by necessity at the time. Not really having a lot of access to like African history and that kind of creating this like void. And like, you know, like I said, I freely consumed martial culture in various forms of media, movies, you know, cartoons, books that sometimes, and it was always like in Asian or it was always European and never connected Africa and people that looked like me to those pictures, to those, to that world concept of a warrior protector or whatever else. And that has always been something I had struggled with my identity in that sense. It wasn't until my eighth grade teacher in Okinawa. Okinawa was a big transformation formative place for me. She was the first person to teach me, to share, to open my eyes to the many, like African empires and kingdoms that existed, you know, in the past. And again, it's always like, it's a seed that's been planted, and it doesn't always just spring, just in that moment. It's usually like she gave me names that stayed here, and then a few years later, you know, when I was, when I had access to, you know look up information to when I, there was this hunger for it. I had those names to use as my reference points. And that kinda like, you know, spread into this like love African history and eventually like the history of enslaved Africans in the diaspora. So now that stuff is kind of like growing on one side, and my martial arts is kind, growing separately on this side. As I'm exploring Jeet Kune Do, I start to gravitate more towards the Jeet Kune Do concepts that's kinda like spearheaded by [00:39:40] and of course, like heavily, a large influx of Southeast Asian martial arts. Which really struck me as very different when I started seeing things like Muay Thai, Kali, and Silat. And it was a very different aspect of Asian martial arts experiencing those. There was something that was like not just like, it was not just like the arts as an art, which was that, or it wasn't even as it wasn't just the arts as how they function. But it was also like art, the martial art itself as being an expression of culture. The incorporation of music and like dance. And I'm not saying that this is not the case in the art in Karate or Kung Fu or you know, the Korean practices, but it seemed a lot more evident in Southeast Asian cultures. So having experienced, experiencing that is what really primed me for like African Martial Arts. Cause the world was getting, like, the world was getting smaller, and what was considered martial arts, and that's what you Jeet Kune Do itself is what opened that up for me. Because, you know, Bruce was dabbling not just in Chinese arts and not just in like, you know, Asian martial arts, but he was bringing in like boxing and wrestling and fencing. You know, Western European Arts into his training, understanding. And so you know, so it was like, well, martial arts is not just an East Asian thing. It's a, you see it in East Asia and Southeast Asia and then in South Asia, India, and then it's also part of Europe. You know, you see it in, you know, boxing and fencing and wrestling. It's even going into the historical reconstruction stuff that we see today. And so it always left me wondering is like wow I could be I wonder if there was anything that was like practiced in Africa. And so in 1993-94, I got my answer, my gateway into the African arts came in the form. Shout out to Shifu Mark Dacascos, Missray Iman Santos for being in Only the Strong.

Jeremy Lesniak:

That's where you were gonna go.

Da'Mon Stith:

Oh yeah. That changed, it changed my life. That changed my life and that was like I didn't even realize like what it was, what was happening. Because we had seen Capoeira before in a movie called Rooftops. Seen it before.

Jeremy Lesniak:

I dunno.

Da'Mon Stith:

Rooftops.

Jeremy Lesniak:

Yeah. I'm gonna write that down.

Da'Mon Stith:

Write it down. Oh yeah. Rooftops and Mighty Quinn. And to be honest, in Kung Fu and David Carradine's Kung Fu.

Jeremy Lesniak:

Been a long time.

Da'Mon Stith:

Yeah.

Jeremy Lesniak:

Trust him. Please continue.

Da'Mon Stith:

Yeah, so I graduated high school in 93 and I had no idea what I was like gonna do with myself, and so I had an extended gap year. Where I was trying to figure stuff out and while I was like free, I was about that martial arts life, you know, I was I got really, really heavy, heavily heavy into Japanese sword crazy. So still doing everything else. For me, when I first saw the Capoeira, there was something that really drew me to it. I didn't understand what I was seeing. I didn't understand the art and the movie didn't really explain the art, like we accepted the art because of the, like the authentic display of it, you know, the display of it, you know throughout the movie or at least like you know not talking about the fight scenes per se, but display of it from the onset of it. So it left a lot of questions for me. Like, you know, what is this art like, tell me, you know, wanna know more about it. Seeing people that looked like me, you know, defy gravity in that way like it was, it spoke to me, you know? Yeah. I used to be a breaker too, so like, I saw a lot of similarity in those movements and I can never dance. I was like, I'm never a good dancer, but I was like, wow. I was like, you know, I was out there and weighing it and throwing kicks and not understanding what I was doing, but I was doing, I didn't have anyone to tell me like, no. But as a kid, as a young person, even as an adult, it's something that I want to learn. Like I'll go, I'll go after it and I try to figure it out. If I don't have a lot of information, like I work with, I have and through my pursuits. Spent a lot of time in bookstores with my mom and libraries with my mom. I came across some like books on the subject of Capoeira and I started to like learn about the art and its history and that really is like what, like opened me up to where I'm at today. You know, so pretty much answer the question for me that there's this fighting art that's practiced in Brazil that is supposed to be based off of other fighting arts that case from Western Central Africa. And not only that, there are a plethora of fighting arts that are similar to this fighting art practice throughout the Caribbean. Practiced throughout South America practice in, even in North America. There's something here. There is this greater, there is this, there during this horrific event of, you know, forced migration of millions of people, when these people crossed the Atlantic, they didn't lose their culture. And this was like the narrative that I felt, you know when I was younger and even when I was like studying, started studying African history, I felt that like, yeah, I wanna focus just on, you know, the time before colonialism, before slavery. Cause I felt like we had lost so much, you know when we had crossed. When I started to delve into the origins of Capoeira and like seeing some of his cousin's art, and just like getting a different narrative to how enslaved people navigated. Slavery and colonialism. You know I think I heard someone say existence is resistance in a sense, you know what I'm saying? Like, survive, like live. And some people found that the best way to combat these things was to be able to like survive to live. Some people found ways to live and disguise what they practice disguise these things so that it would survive. Some people said, hell no, I can't live like this. We don't, shouldn't live like this. And they physically stood up and fought, you know what I'm saying? And these are all ways of resistance and these are all ways that have their time and their place. But just knowing that there were alternate narratives out there and that it wasn't always the case of, you know, just being in the position of weakness, you know, it's like I didn't like feeling that way. So really opened me up to like the different ways that enslaved Africans resisted slavery and took mastery over their bodies through the practices of this art. And, you know, even, you know, like from in all these degrees of like whether it's like open revolts or if it's like, you know, Brazilian culture is like, you know, Afro-Brazilian culture is Brazilian culture, you know what I'm saying? It's like, it's one of the, it has like the largest number of people of African descent in many, many African nations. And so I'm not saying any of that perfect, but you know, it just opened my eyes up to the different ways that, you know, different stories.

Jeremy Lesniak:

Sure.

Da'Mon Stith:

So by seeing all that that was happening in the diaspora, the next question, the next logical solution for me was like, well, what are the parent art to these things? And then that led me, you know, to researching continental arts so.

Jeremy Lesniak:

Now I would imagine that you know, if we're doing the math here, you're talking about coming out of high school in ‘93, and you know, from my vantage historical European Martial Arts that work, you use the word reconstruction didn't really happen until the internet got bigger, right? There were people doing it, but it was just, it was so niche.

Da'Mon Stith:

Yeah.

Jeremy Lesniak:

I would imagine you found the same challenge. How do you put these pieces together when they're scattered? And let's face it you know, there aren't a whole lot of people. Asking the question, well, if martial arts existed everywhere, which I think we can all agree if anywhere that there might have been more than a few people, there was probably gonna be some fighting and somebody was gonna be smart enough to say, well, maybe if I get better at fighting, I won't die.

Da'Mon Stith:

Right.

Jeremy Lesniak:

What did their fighting arts look like versus their fighting arts?

Da'Mon Stith:

Yeah.

Jeremy Lesniak:

And over the last few years of this show, we've had the opportunity to hear a lot of these stories.

Da'Mon Stith:

Right.

Jeremy Lesniak:

But I'm curious what your early explorations into you called them Colonial.

Da'Mon Stith:

Yeah.

Jeremy Lesniak:

Is that what I heard you say? Colonial? What was the word you were using for the parent arts or Capoeira?

Da'Mon Stith:

No, no, no. The what did I use? Don't remember the exact term.

Jeremy Lesniak:

That's ok. That's ok. Talk about that early research you were doing.

Da'Mon Stith:

Yeah, yeah. Yeah. So, it's the same, it's like, as you described like I got a point where I had, I was doing research both in the early phases of the internet and then I was doing a lot of book researches as well, and then a lot of interviews and asking and talking to people. So we're right now probably at 1997-98 I'm on UT, the University of Texas campus. And I start off there actually with the African Students Association and, oh, lemme back up. So Capoeira and then I come across a few, so I come across a few videos and articles about African Americas, who were researching and doing African Martial Arts. And that led me primarily to like the work of Kilindi Iyi. He's passed away fairly recently. And what really struck me about his movements? As you know imagine I'm also coming from like a Southeast Asian background. At this time the use of weapons like in Karate you couldn't touch weapons, like until you got to like a certain phase.

Jeremy Lesniak:

Sure.

Da'Mon Stith:

But in like Silat or in Kali, you know, you're picking up weapons in the beginning. So I like…

Jeremy Lesniak:

Yeah.

Da'Mon Stith:

The emphasis on using weapons which he demonstrated like, you know, the use of like, you know stick fighting, wooden weapons that were like spears and, you know, war clubs and things of that nature, and using these things in the training. And so I'm like, wow, you know, this is like really cool. Like, you know, Capoeira was one thing. But then seeing this was like, ok, this is really like ok. You know for Capoeira it's like, it's as a martial artist, you know, fighting is kind of part of what we do, whether that's like for fun or just for the exploration or for the personal challenge or whatever else. So like, I was still figuring out how Capoeira felt, fit in to as a fighting art, I'm still figuring it out for myself. And initially, that's what, if I backtrack a little bit, what really made me make the connections is seeing the move, the commonality of movements between Capoeira and like Silat and like Kali in certain aspects. So that it kinda made me, you know, gravitate to it at least like seeing it outside of, it's like outside of traditional play, traditional you know, the expression of it.

Jeremy Lesniak:

Right?

Da'Mon Stith:

Just talking about it as like a fighting art. And so what I liked about what he was showing was like, it was lots of, it was weapons training, it was like weapons based, it was a wrestling component to it as well as striking. And so I got his videos and reached out to him and he was demonstrating, like Zulu stick fighting, he was demonstrating long stick from Egypt and then he was doing you know his empty hand stuff that was based off of risk night fighting. And so, well, what he was doing, there was like a, there were, and there was like also movements that were like encoded into the dance, into traditional dances. And so that was very intriguing, you know, to me.

Jeremy Lesniak:

Yeah.

Da'Mon Stith:

That approach. And so I kind like, again, I follow up on those leads. Looking into in going stick fighting, a little stick fighting. Arts like Tahtib which is where the Nambot, the stick practices that he was using was coming from. And you can find what we call like living traditions today. It's like, you know, cultures that have maintained or revived their fighting arts. And so I would do research trying to find those roots because he, no, so I'll say this. So what, Africa is a very large place, right? A very large, very dynamic place. And the issue I came across when trying to like find African Martial Arts is actually the words I'm using, right? If I say African Martial Arts especially then, then I'll go to the university and I'll talk to people who come from Nigeria or anywhere else. They're like, you know, African Martial Arts, what you talking about? What do you mean? I wasn't using the right words, I wasn't framing it in a way to get, you know, information I needed to be more, I'm using it as an American, using the term martial arts. I should be using more specific terms. Like, well, is there any type of wrestling? Is there any type of, you know, things like that, more specific stuff can get better answers that way? But I had to learn that by through talking to people.

Jeremy Lesniak:

Ok.

Da'Mon Stith:

But case in point.

Jeremy Lesniak:

Yeah.

Da'Mon Stith:

So I did this demonstration for the African Students Association after like being inspired by Clint East videos and then like, my time with Capoeira, and kind of like this opening, this dialogue about African Martial Arts. And for the most part, it was well received. Many people didn't really have any much to contribute, but through that dialogue, like I met a student who was a, he was from Togo. And he was a, he was actually writing a paper on Togolese wrestling called wrestling festival called Ivala, and the comparison between Togolese wrestling and, you know, wrestling arts like Judo. And he came and taught some stuff and demonstrated some stuff in my class. And so it was that kinda like synergy that I found. Sometimes it would yield things like that. Sometimes it would yield only a word or a description or nothing, but that was the way of it, you know. So it was between talking to people, interacting with people, finding sources online, and like reading books on this on the subject where I started to get a little bit of momentum. But I started at that time lean more heavily into and then of course, as the world became more connected, it created more opportunities to make connections.

Jeremy Lesniak:

Ok. Where did you go from there? I would imagine at this point you have far more questions than answers. And you know, it sounds like you're spending time with Capoeira almost cause you don't know where else to spend it.

Da'Mon Stith:

Yeah, I had a friend who helped me, like put our Capoeira group together and we were both like fans of Kalindi Iyi work and we were like, yeah, so let's, we're gonna focus, we'll focus on Capoeira, Zulu stick fighting, and Tahtib. Those three were like the most accessible that we could do. And then, eventually, the emphasis became more on Capoeira. And partially because I feel like Capoeira's success in the world has actually made it possible not just for me to do what I'm doing now, but I think the Capoeira's success has allowed for other arts in the African diaspora to like gain momentum locally.

Jeremy Lesniak:

Sure.

Da'Mon Stith:

Many of these arts at that time and before were you know, pretty close to extinction in many aspects. And then you see like this, revitalization that happens and I do believe that Capoeira again, being as popular as being as widespread, helped to say, well, there is Capoeira here. But there's an art that's very similar to it that's practiced in this little island called Martinique called Damier, and it's like, oh, wow. They do punching, kicking sweeps, headbutts, throws, grappling, standing, and on the ground. Wow. And then so you're like, you know, it adds this forward push just like hunger that feeds into the development and the revitalization of these art forms. So I really think Capoeira fueled this current state that we're in.

Jeremy Lesniak:

Yeah.

Da'Mon Stith:

I knew that there was more out there. But again, not always having like the access to it and Capoeira being more accessible. That's where I put a lot of my attention into, you know, as things started to you know again they say the teacher, when a student's ready a teacher appears. So it was constantly a case of that where I'm actively training Capoeira. Trying to keep on my weapons skill, but again, putting a lot of focus in on Capoeira.

Jeremy Lesniak:

But at that time your weapons skill was primarily Japanese, right?

Da'Mon Stith:

Well, I had, so lemme go back.

Jeremy Lesniak:

Ok.

Da'Mon Stith:

Yeah. So I had stopped focusing on Japanese sword. So it ok. Actually, yeah. This in like, I knew it. So I went through about a year of like this intense Bushido Kenjutsu phase. It was pretty crazy. probably write a movie about it. And then I mean, I was like pretty bad. Like, I was like serious about it. Like in a very yeah, like I would carry my bulking around. Like I was pretty damn serious about this. And then I think that, like, after about a year of doing that, I was like, well, how practical is it for me? Like, you know, like, I mean, am I really waiting for ninjas to jump out the forest? And blow my bulking out, I was really serious about my stuff, but, so I started to I stopped training. I stopped practicing Kenjutsu, and that kind of gave way into like the holiest scream of the night, the knife, and the more, more the knife than it was a stick. Then I could carry a knife around, which then I got into Dune, and then it's like framing and carrying knives. It was like, it was just like this thing that kinda like, you know, kept me going. So by that time,

Jeremy Lesniak:

How many knives were you carrying?

Da'Mon Stith:

You know, I…

Jeremy Lesniak:

This is something I've only recently learned among Filipino martial arts practitioners that you can never carry just one knife.

Da'Mon Stith:

Yeah. Yeah. Like there was a store, these two stores, the internet like internet sales killed these stores. They were like, it was a martial arts studio with multiple rooms. It was a perfect setup to be honest. Martial arts studio with multiple rooms teaching multiple arts.

Jeremy Lesniak:

Oh, cool.

Da'Mon Stith:

There was a bag area where you can just pay a flat rate a month and it's work on the bags. Right. It had storefront they sold weapons, videos, gear and geese, and stuff like that. It was a perfect set. I would like to see those kinda things come back.

Jeremy Lesniak:

Yeah, me too.

Da'Mon Stith:

So yeah, so they would sell knives to the kids, to us you know when I was 17, 18 probably shouldn't have been walking around with some of these, but they were like you know, I had all these like really exotic swords and stuff and we would go get our knives and stuff from them. But yeah, I had, I think I had at that time just, just one knife I was carrying with.

Jeremy Lesniak:

All right.

Da'Mon Stith:

Yeah, yeah, yeah. I wasn't that deep into it. There was a point in when I was like, I have to have seven weapons on me you know. I had a knife and I had you know I had my hair back, I wore this like little spike.

Jeremy Lesniak:

Oh yeah.

Da'Mon Stith:

My hair had a chain it was like I don't know what's going on with me.

Jeremy Lesniak:

You were ready to go.

Da'Mon Stith:

I was ready to go. So yeah I, from that point, yeah, I had was favoring the knife over the sword, just kind of out of this like this practicality you know of being able to carry it. And that's kind of where my shift and focus went. And I think, and I don't really think I honestly started to like, carry a blade until like, I was like, maybe like 19 is when I was like, I had a small little blade, little fixed blade that I would carry. But yeah, my, basically my focus had shifted from the katana to like something shorter and close and stuff. I felt that was more practical. You know, again, not that I'm getting into night fights and like you know whatever ever else but in my mind that's what I was that's where…

Jeremy Lesniak:

It's a lot easier to carry a 3, 4, 5-inch blade than to carry a sword. You walk down the street with a sword and people are gonna call the cops.

Da'Mon Stith:

Yeah. Well now in Texas it's perfectly legal.

Jeremy Lesniak:

They're still gonna call the cops.

Da'Mon Stith:

They're still gonna call the cops, true. But yeah, so, and I think I'm trying to go back, it's a little fuzzy sometimes for me.

Jeremy Lesniak:

It's ok.

Da'Mon Stith:

At that time I was trying to adapt the stick and show method of a Zulu stick fighting and then like the long stick work that was from Tahtib which you know, so many of these practices, they occur like and that goes back to what I was trying to say earlier but I think I went around and circle back here. So going back to like how we define martial arts and what we expect from martial arts as a pro, martial arts as like Americans or even as like, coming from outside the culture. Some of these combat sports, these warrior traditions, they happen for very specific reasons, right? It's not quite like, you know, say that you are you're a, you know, from the Suri tribe in Ethiopia, right? They're renowned as stick fighters. They fight with these really, really long sticks, and they're pretty hardcore, you know the fighting is pretty hardcore, you know, it's not uncommon for, you know, limbs to be broken and things of that nature, but the Suri don't use, at least like today, nowadays they don't use stick fighting for self-defense. They do it for very specific, what's that? Yes, AK 47 is what they use self-defense now. Thank you, Jay. He's right though. Yeah. They have conflicts with other people and they're using guns.

Jeremy Lesniak:

You're not bringing a stick to a gunfight.

Da'Mon Stith:

No, not at all. So that form of stick fighting exists within that particular timeframe, that particular ritual for that particular people. And so each ethnic group will have a specific type of fight. Dambe Boxing, for example, you know, it is from Nigeria is specifically practiced by the house of people in northern Nigeria. And it's their cultural practice. So a guy a Dambe boxer may not use Dambe boxing. If they get into a fist scuffle, I'm sure it helps in certain aspects, but it's not the same way that we're viewing it. This is not to say that there aren't some arts that are like that, because again, we're talking a bit about a very, very large and diverse, group of people and a very large and diverse, you know, practice. So they're not all, all the same. Typically with African Martial Arts, we notice that they function on a societal level to whether that's to like, I should say, not just to like train people to be fighters, but also like as a source of entertainment. As a means to celebrate certain like Rites of passages, to celebrate or commemorate the ancestors of certain spiritual celestial alignments, and things like that. Depending on the culture, this is the significance of some of these activities. So like as a, even though I'm of African descent when I do like Suri stick fight, it doesn't have the same cultural significance to me because I'm looking at it as I'm not looking at it as this is what I'm gonna do in order to like prove my bravery and demonstrate my skill and be able to like gain access to choose my wife. That's not why I'm doing it. I would do Suri stick fighting, so all I have a long stick tradition that I can draw from. That means I can play with other martial artists that fight with similar weapons. You know, or if I needed to or if I wanted to use it as like a means of self-defense I could, so like my using it is a little different. And so like there is that, that kind of understanding that has to be, we have to come to that kinda understanding when we are exploring these arts is that they take place in a very, very specific, you know, specific way. And so that raises different questions for people who are looking for African Martial Arts and how you go about doing that. Like, you know, it is a question that we're still as the African Martial Arts community still trying to like answer, and then some people take you know very very hard lines one way or the other on like how it should be done and what should be done.

Jeremy Lesniak:

Shocker.

Da'Mon Stith:

Yeah.

Jeremy Lesniak:

Right. Subject to the martial arts with hard lines.

Da'Mon Stith:

Yeah. And my way is to be as open and honest as possible with who I am and what I do and in being open and honest with the material. If I'm doing, you know, like I have a mentor and a teacher in Algerian stick fighting the Matrag. And I'm very clear each one of these things has its own, and I say traditional, but I mean, traditional is not the right word, but I'll say cultural way that it's like, and I use the term played. So it has, its cultural way that it's played or performed or fought that exists within inside that particular culture. It would be like in Karate doing the same system, like maybe one-step sparring or a particular contest. This is within those systems. What I'm doing is two things. I want to preserve the practice as I've received it, paying respect to the way that I received it. At the same time, I wanna be able to do that on one end successfully and faithfully do that. On the other hand, I want to be able to take it and explore with other people that are outside of this realm. So with this stick fighting tradition I can you know because it was a means of training and preparing soldiers to use sabers and swords and things of that nature. So I can now, I can take these skills and I can interact with other people that fight with sabers or other people that fight with medium link sticks, or people that do different arts. I'm now able to, oh, this is a skill set that I've learned from Matrag and I'm coming to explore and interact with you guys that are doing this HAMA Saber tournament. So or if I'm you know, going to enter into a Gianfa, you know, sword Tournament, I will take those skills and explore my sword stick skills with people that do Gian fighting. And that allows me to interact and to expose, you know, one myself and get that feel as a martial artist, I don't wanna, I wanna be, I wanna have my root, but I don't want, this is me speaking. I wanna have my root, but I also want to be able to like, expand, you know, beyond the root. And so this is my way to do that. At the same time, if I make a good showing of myself, if I fight with honor, if I fight well, then it's like, oh, what are you doing? What system is that? What are you training? And then I'm, this is what I do. This is where this comes from. And then it's like, oh, I never knew that this existed. And then there's this like exchange and this dialogue that happens. And that is what I'm trying to do.

Jeremy Lesniak:

I love it. I love hearing that. I've talked to very few people who feel strongly about doing both the preservation of how it was given to them for historical and or cultural and or respectful, you know, whatever reasons. But also allowing it to exist in a separate way. You know, you've got one and the other, and this one over here can morph and change and grow and, you know, become something else.

Da'Mon Stith:

Yeah.

Jeremy Lesniak:

And I've always appreciated that dichotomy because when it happens, it both solves all the problems, right? We can still have this, I can show you the way that I was taught my katas growing up in karate, but I can also show you how I adjusted them when I took them in the competition.

Da'Mon Stith:

Yeah. And I think that that's what, that is the dilemma that martial artists find ourselves in is like honoring tradition, but also, realizing that like life, fighting is dynamic and chaotic. It's not static. And we can always have our roots, we can always have our traditions, we can always have our source, but we can also, you know, fulfill. And that has been my thing is like there is a desire in me to like have and know that this tradition existed and to be fed by it. At the same time, there's also this need in me to like you know, find myself in this larger world to be like a living, breathing you know, martial artist, you know what I'm saying? And that is the challenge I get sometimes from, and I've had, and I'm very blessed to have very few you know, critics in that sense. But I think that that's one thing they don't understand about me is that even with Capoeira, you know, and I'm sorry I'm bouncing back and forth.

Jeremy Lesniak:

It's ok.

Da'Mon Stith:

Even in Capoeira when we see Capoeira play today, if we just say, oh, this is Capoeira, this is the way that it was done since it was created, it's never changed. It's never evolved. It's never adapted. It looks exactly the same. It's been perfectly preserved now from back then. And that's like, that's not true. It has changed. And so when you get people who kind of see it in that way, and this is not just for Capoeira, and then you say something like, well, I wanna explore how, like I hear all these stories about these guys who would fight against the, you know, the armed police, the military police, you know, in the 19 hundreds. All these, like, you know, these guys that, you know, this guy was legendary Capoeirista who could fight, you know, 10 guys, 10 armed guys that didn't disappear. You know, like, I know that that part is not true. That him turning into like a Beatle and disappearing is not true, but like there had to some substance to this story. Or like when the Hessian and Irish mercenary battalions in Rio revolted because they weren't getting paid correctly. The government in Rio who had been persecuting, like Darth Vader-style Jedi persecuting Capoeiristas. They weren't persecuting them because they were turning flips and singing songs and disguising their fighting art as a dance. They were persecuting and imprisoning them, killing them, exiling them, and practicing their art because they felt that it was a physical threat to, they were like paramilitary groups in a sense. So the City of Rio called in the Capoeiristas to fight against the Hessian and Irish mercenaries and the city. Then they say the city from these two groups. And so, like, how is a, I mean, in many ways it could happen, but how is a group of people who aren't practicing a legitimate fighting art, how are they able to contend against, you know, modern full-time military, you know, well trained military organization and, you know, so like it, hearing those kinds of stories, it's like, well, ok, well how does, how do we do this? Like, how does it look? What does that look like? So even coming from that kind of perspective is like oh yeah, you're kind like, you're a breaking tradition. You're violating tradition. You're not, you're adding like foreign influences. You're doing this and you're doing that. No, I'm really just trying understand like how, if you and you that these are the artists that were practicing the Quilombos when they were fighting against the Portuguese and the Dutch. Well, how like tell you know when is this you know what is it? How does it look? Like how does it look it is done that way? And so just kinda coming out the box in that kind of way it's like you know you get criticism and stuff, and I've just come to accept that that's, this is just my path.

Jeremy Lesniak:

Here's how I look at it and I dunno if you've ever thought about it this way. All fighting arts and the easiest place to see this is in competition. All fighting arts end up being somewhat specialized towards whatever the rules are. Ok? So if you take out the rules, what are the rules? The rules are the terrain, the height of the person. Are you fighting one-on-one or group-on-group, or are you being ambushed? Or are you ambushing?

Da'Mon Stith:

Right?

Jeremy Lesniak:

What are the weapons that are involved?

Da'Mon Stith:

Yes.

Jeremy Lesniak:

Are you fighting during the day or at night? Those parameters are going to exist regardless. So if I take TaeKwonDo and I try to understand TaeKwonDo from, actually, it's a bad example cause there's a book. If I try to take karate, you know, some Okinawan flavor of karate from however long ago and try to understand it as best I can, I need to mimic the environment. I need to have similar styles of training and dietary concerns, right? Because certain things work when you're bigger and more muscled.

Da'Mon Stith:

Right.

Jeremy Lesniak:

That don't work when you're on the verge of starvation.

Da'Mon Stith:

Right.

Jeremy Lesniak:

And so when people say, well, no, that you're corrupting it by trying to inject these other things. I see it as let me try to understand it from the inside and the outside.

Da'Mon Stith:

Right.

Jeremy Lesniak:

And it makes complete sense to me because if you are being true to the historical elements, those parameters.

Da'Mon Stith:

Right.

Jeremy Lesniak:

You're gonna have a better under, oh, ok, well they wouldn't have done this because of.

Da'Mon Stith:

Right. Right.

Jeremy Lesniak:

Instead of saying, no, there's no way that these people could have thought of doing a kick in this way or a punch in this way. To me, that's incredibly arrogant when people make that criticism.

Da'Mon Stith:

Right. Right. Exactly. Yeah. And I think that's what I enjoy about where I'm at now is like, I feel more like a scientist in a sense. That like, you know, even just what it takes to kind get like a rough idea of like what this could have possibly be done. It involves, like one my body, getting my body, making my body prepared to do what I think that they were doing. Right. So take for example, say I'm and one of the things I work on is like Egyptian martial arts. No, there are no books on them. There's no living traditions of ancient Egyptian martial arts. Tahtib probably being the closest in Egypt itself, but so I know that Egyptian soldiers, they practiced stick fighting, multiple modalities of stick fighting. They fought with shields. They fought with weapons, they wrestled, they practiced archery. They ran this is the thing that they did. So part of getting my body together is doing those things, you know what I'm saying? Doing my size, preparing those things. I may not have all the answers of what it looked like, but I can prepare my body for the task. I know that if I have to carry a shield, I should probably have some kind facsimile of a shield that I can like practice with to develop the strength and muscles to able to do that. If there were swinging, you know, cutting, smashing. Percussive instruments like maces, axes, and slashing swords. Then I know that those, I know the activities I need to do. Outside of that, I'm looking at a lot of like art. I'm looking at iconography. I'm looking at statuaries both from the time period and from also from contemporary cultures that have either been influenced or may have influenced the culture that I'm studying. I'm also looking at living traditions that are still practiced in the areas, in the immediate areas that are like you know, close to where the Egyptians were. The Nuba people in Sudan, I think that they have like a martial culture that closely resembles those of pharaonic Egypt, the Nuba are renowned as wrestlers. They have various forms of stick fighting. Most notably is they do stick fighting with a strapped shield on the forearm, like a plank on the forearm. And a medium link stick is like, it's almost parallel for, you know, middle kingdom stick fighting at the time. So, and I'm looking at, you know, these contemporary living traditions that are still practiced in Africa or in the Middle East. And this is like allowing me to like, kind of like narrow down. I'm looking also at the like I said, there's no there are no manuals, no books on Egyptian martial arts or how to use khopesh, but there is a very detailed surgical manual on how to treat like people that have suffered very traumatic wounds. So, and a lot of the wounds are like pierce being, you know, stabbed by spears or by swords and things like that. Like I'm doing this whole forensic…

Jeremy Lesniak:

Yeah, really cool.

Da'Mon Stith:

And at the end of the day, I'm not gonna say, well, this is the art that was taught by you know, Thug Moses the Fifth, you know, and it was passed down to me and so and so, and so and so. No, I'm like, this is what I'm doing. This is the best reconstruction that I can do based off of me preparing my body to be able to deliver, preparing my mind by acquaint, by becoming very, very acquainted with Egyptian military traditions, being very acquainted with Egyptian weapons, defensive gear, what their contemporaries were using and doing at the same time, and what living evidence we might have from living traditions around the area, or people that have, or cultures that have similar tech. As like the Egyptians did at the time. And like, you know, I'm counting on being wrong and that's ok because it's like, it's always something new that adds to it. And I'm always constantly learning. I'm constantly growing. I'm never like the master in that sense. I'm always like a very avid student and I like that.

Jeremy Lesniak:

Nice.

Da'Mon Stith:

But we're gonna start to wind down. I wanna make sure that we talk about your swords though. Cause I know that this is still a passion of yours. It throws back to the very first thing you talked about. What's going on with swords and what would possess someone to invest time in making and testing swords?

Jeremy Lesniak:

Say that part one more time. I'm being harassed right now.

Jeffrey DaShade:

Because you sure look like a master to me.

Da'Mon Stith:

Oh my God. Well, that was a reference to The Last Dragon. My friends are goofy, sorry.

Jeremy Lesniak:

No, it's a good thing. You have goofy friends.

Da'Mon Stith:

Clearly. So what was your question one more time?

Jeremy Lesniak:

You invest a lot of time into swords, just in all the ways that one could invest time in, right?

Da'Mon Stith:

Yeah.

Jeremy Lesniak:

Researching, understanding, training with making, and I imagine that there's some parallels there with the research that you're doing as well. So I wanna make sure we talk about that before we wrap up.

Da'Mon Stith: